Three highly effective productivity hacks for dealing with unstructured time

The last 18 months have been, without question, the weirdest I've ever experienced in terms of my professional life in my entire 21+ year career in higher education, because of two things:

- My year-long sabbatical at Steelcase, where I was out of the classroom and all other elements of facutly life from May 2017 through August 2018; and

- My recovery from open-heart surgery (which happened on February 6), currently ongoing, which thanks to FMLA leave has me out of faculty life again until the middle of April.

So I have only been engaged with a normal faculty schedule of teaching, scholarship, and service for about four months over the last two years.

And yet, during all this time --- except for vacations (not terribly common) and the first two weeks after surgery --- I've had to get stuff done including research projects, long-range planning for classes, work related to being Assistant Chair, side projects related to professional development, and more. And unlike a normal faculty schedule my time has been completely unstructured. At Steelcase, I came on-site three days a week; when I was there, I usually did not have any particular place to be at any particular time but was left to my own devices to choose where in the building I was going to work, and what I was going to work on. As I recover from surgery, I have to stay around the house (no driving for another couple of weeks) but my day is completely open to structure as I choose.

As I've worked in these unstructured environments, I've had to learn how to straddle the line between sloth on the one hand and overwork on the other, and I've been successful, I think: I finished a 50+ page research article, completed a Data Analyst track on DataCamp, planned my department's course schedule for 2019-2020, and a lot more. I've had to learn how to impose structure on my time and motivate myself to be productive, and I wanted to share the three productivity strategies that have really made this work for me.

Strategy #1: Timeboxing

Timeboxing is simply the process of taking chunks of work --- either single tasks, or a predefined group of tasks, or a project --- and assigning them to a fixed "box" of time during the week, and working on in single-mindedly without distractions during that time and not working on it outside that time. For example, when I did my weekly review this week I set aside a one-hour box of time from 11:00am to noon on Thursday to work on this blog post. And right now that is what I am doing; and I am not doing anything else, including checking email or getting coffee or working on another task.

We faculty (who are in a regular faculty schedule, unlike me) already have timeboxing built into our schedules in the form of classes and meetings. We don't have the option of spending 2 hours on a class that's scheduled for 50 minutes, and that's good, because it forces us to use that class time effectively. Carrying the same scheduling idea over to tasks and projects that are not inherently time-bound similarly injects energy, focus, and efficiency into them. Creativity loves constraint.

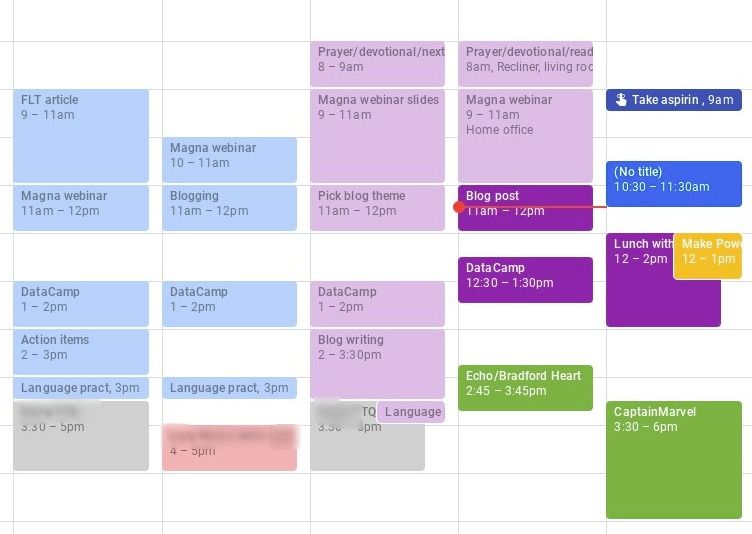

I used timeboxing at Steelcase to impose a schedule while working on site: A 9-11am block on Monday for working on our literature review, 11am-noon the same day for meeting with a client, a standing 3-4pm block every day for clearing out inboxes and setting up my agenda for the next day, and so on. I do the same thing now while I'm homebound recovering from surgery. Here's this week for instance:

I set up all these boxes during my weekly review every Sunday and just put them in my Google Calendar. A lot of these boxes correspond to the Big Rocks for the week, which I make sure to schedule time for. For me, this is enough structure to keep myself mentally active and moving forward, but not so much that I am stressed out.

Timeboxing was rated the #1 productivity strategy recently for a reason: If we don't impose some boundaries on our work, our work on those tasks and projects will just keep expanding to fill the time that is left over in our week. If we don't impose our will on the time we have, in other words, the time will impose itself on us.

Strategy #2: The Pomodoro technique

Maybe you feel the same as I do sometimes when it comes to work: I have a well-structured weekly schedule and a good idea of what I need to get done, but when I sit down to work I find I have no motivation to actually do anything. To help myself get past this, I adopted a little hack known as the pomodoro technique. All it takes is a timer and a list of things to get done:

- Decide on the task or group of tasks you want to get done.

- Set the timer for 25 minutes.

- Work on the stuff you decided upon in step 1, with no distractions and no sidetracking. It helps to shut off all email, social media, text messages, and so on before the timer starts.

- When the timer ends, stop working and record what you did.

- Take a 5-minute break.

- Repeat steps 1--5.

The "official" version of the technique has you work through 3-4 of these "pomodoros" and then take a longer break, then start over, and try to complete as many pomodoros during the day as possible. It's called "pomodoro" because the person who invented it used a tomato-shaped kitchen timer (see above). But you can use anything that keeps time; I like this Tomato Timer website.

The pomodoro technique is similar to timeboxing on a micro scale, because we create boundaries around work where there were none before, and bring significant focus to our tasks inside those boundaries, letting the pressure of the boundaries push us further along than if we'd had no boundaries.

The pomodoro technique for me has been the missing link between organization on the one hand and productivity on the other. My GTD system has been great at being an information system that I can query to find out exactly what I should be doing at any given time or location --- but it's not been great at getting me to actually execute what I need to get done. Putting additional time boundaries and making sort of a game out of it, has helped me get better at the Doing part of GTD.

Strategy #3: Kanban for complex projects

One thing I have learned about work in the last year is that there are two kinds of projects: simple and complex. In GTD language, recall that a "project" is just anything that needs to get done that takes more than one step. Sometimes my projects just need to be broken down into a list of tasks that can be completed in a roughly linear order. But I also have projects where, once broken down, the tasks move independently and flow between a state of needing to be done, getting done, and being done. An example of a simple project is writing this post; it just involves outlining, drafting, editing, and publishing in that order, and nothing more. An example of a complex project is preparing for a speaking engagement, where there are multiple kinds of subtasks (tasks related to travel planning, tasks related to preparing the talk, etc.) and they aren't just ticked off box by box.

For complex projects, I've found that a kanban board works wonders. Kanban originated as a scheduling method in Japanese manufacturing facilities. It's very simple: Individual tasks are represented by cards (physical or digital) and those cards live in one of three lists: To Do, Doing, or Done. Modern versions of kanban boards can be more complicated than this, and kanban is the basis for the Agile project management philosophy. In fact it was while I was at Steelcase that I came into contact --- constantly --- with Agile, even took a two-day course on Agile and started thinking about how Agile could be scaled to work with individual faculty projects.

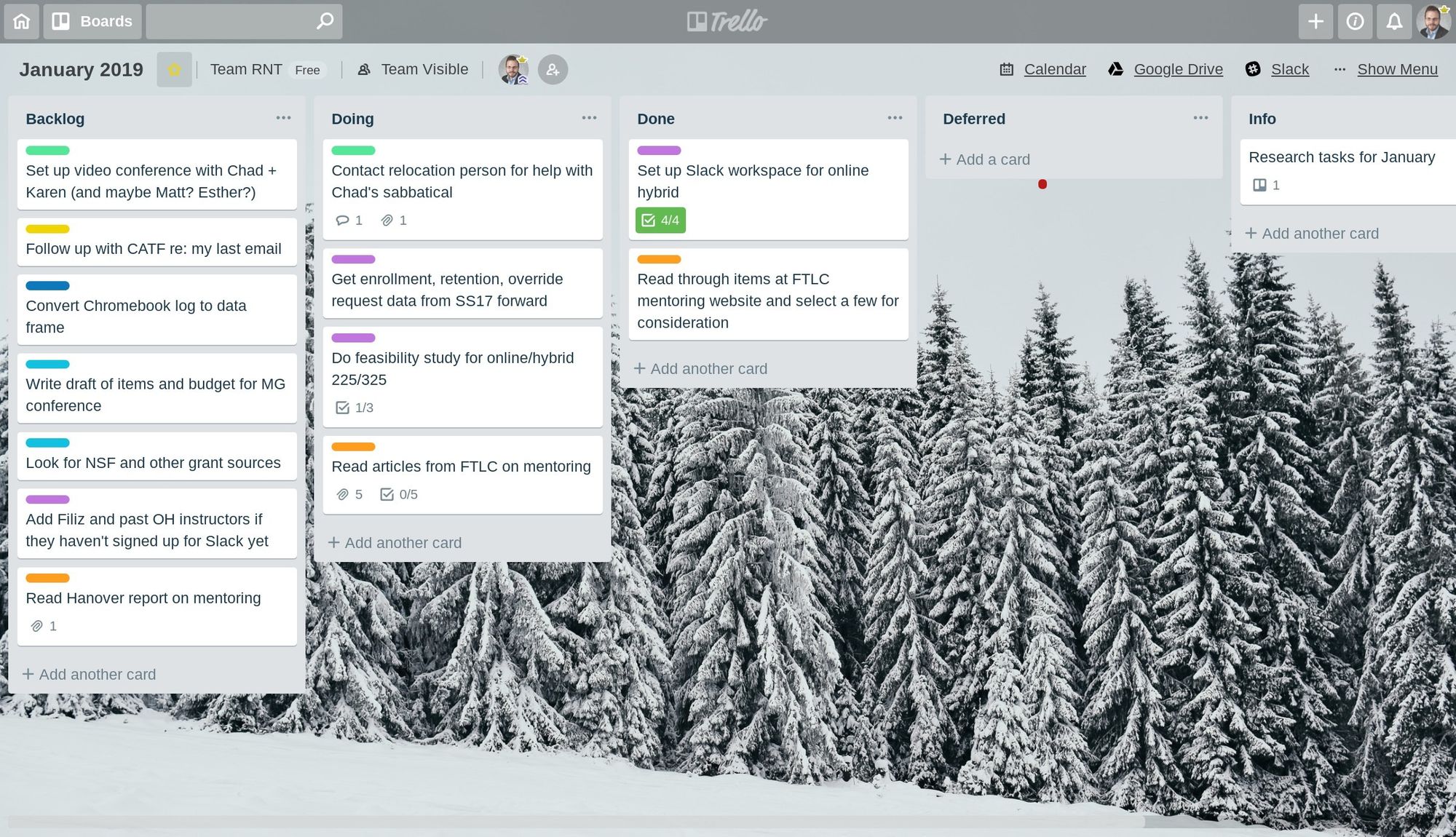

I started using Trello to set up simple kanban boards for complex projects. Here's the one I first shared in this post where my complex project was cramming all my semester activity into January so I could have it all done in time for my FMLA leave:

When I start working on a task, I move the card from "Backlog" to "Doing". When it's done, I move it to "Done". If I have to delegate it or otherwise enter a waiting period on it, I move it to "Deferred". You could just as easily do this on a physical wall or whiteboard using sticky notes. The board allows me to see the state of all the tasks in the project at once and have a sense of the overall progress on the project.

It's again another instance of imposing structure on something that doesn't have structure naturally attached to it. And there's something quite satisfying about physically moving those cards --- I'm really asserting control over those tasks and literally pushing them around, rather than being pushed around by them.

One question someone might have is whether these techniques would work for faculty who have incredibly full schedules and little control over their time. I would say two things. First, yes, these do work when you have a full schedule --- I know because I was using these not only during my "off times" in the last several months but also in Fall semester when I had a very busy schedule.

That gets me to the other thing I'd say: I'd caution against falling into the trap that we faculty think we have no control over our time. We actually have a lot of control. We have time in between meetings and classes that is ours to choose how to use. It doesn't have to be all spent on grading, in fact it can't be because we have more than just grading to do. And we also have the ability, even the responsibility, to say no to things in order to protect the time we have and be fully present for what we need to do. To the extent that we can impose our will and our choices upon time, we need to get into the habit of doing so, and these techniques are really helpful in making the most of what we have --- even if it isn't much.

This blog now features Disqus comments! So share this on social media and/or tell me your thoughts and questions in the comments.