Working in a semester that's one month long

I am currently having the most unusual semester that I've ever had in 21 years of teaching, or am likely to have for the rest of my career. As many of you know, I'm about to go on medical leave from my work at GVSU to have heart valve replacement surgery. This is an open-heart procedure with a 6-8 week recovery period, and so I've scheduled my FMLA leave to run from February 6 through April 5. What this means for me right now, is that I don't really have a "semester" this time: I have one month at work, then two months completely away from work, then 2-3 weeks back. And I have no teaching (the one class which I was scheduled to teach this semester has been given to another faculty member), just administration and research. So everything is blown up and nothing is as it normally is.

It turns out, though, that this has its benefits --- and this weirdly constrained schedule is teaching me a lot about doing work well.

I've written before in other contexts about how constraints can lead to improvements in your productivity and referenced Marissa Mayer's talk about how "creativity loves constraint". My current situation is constraint writ large. Coming into this semester, I had a fairly long list of things I wanted or needed to accomplish in my role as Assistant Chair and in terms of research:

- Complete the merit review process for departmental faculty (a group effort, and a nontrivial one since we have 30+ tenure-track faculty)

- Lead a task force on measuring creativity in upper-level math courses

- Coordinate all the online and hybrid courses in the department, including conducting external evaluations, authoring new course proposals, and collecting and analyzing enrollment/retention/grade data

- Figure out how to centrally manage the department's fleet of Chromebooks for class usage

- Coordinate an upcoming sabbatical visit by a faculty member at another institution

- Take the lead in revamping the department's faculty mentoring process

- Finish up three research projects from my sabbatical last year

All of these had previously been filed under "things to get done in Winter 2019 semester". And they still are. It's just that now, my Winter 2019 semester is four weeks long instead of 14 weeks. I have until February 5 to all of these projects either to completion or to a point where they can be safely handed off to another person or tabled for two months and then picked up again and completed by the end of April.

Lest this sound like complaining, I actually requested a later surgery date than I could have scheduled, precisely in order to have one solid month to get all this work done. In my view, what I have given myself is an intensive four-week sprint to do my work. I am now one week into this sprint, and far from being exhausting or unmangageable, I think it's been one of the most productive weeks in recent memory, and I feel completely on top of everything I am supposed to be doing. I have a sense of forward motion, of positive momentum and clarity, that I often lack during "normal" semesters. And this has got me thinking more about the important role of constraints on my work.

I'd say that so far, I've learned or freshly realized three things:

- Having boundaries on your work is good. Whether it's time, resources, or any other element that is needed for work, constraints on these tend to inject energy, clarity, and creativity into what you're doing. When my time to completion of any of these projects shrinks from 14 weeks to 4, I suddenly don't have the luxury of a leisurely timeline, or of having no timeline but just kicking the can down the road. And on a schedule this compressed, I have to think creatively and not trust that how I might ordinarily do things on a 14-week timeline will still work. This is all highly beneficial to me and my work because it forces me to think fast, stay in touch with what I'm doing, and actually get things done.

- Where there are no boundaries or structure on your work, it's critically important to impose them yourself. Most of the projects I just described did not come with instructions. This is the case for most academic work. In these cases, and on this timeline, there are three very important ways of imposing structure on free-form projects.

- Every project must be broken down into parts; each part broken down into atomic tasks that can be completed one at a time; and one task from each project has to be designated as the next action that can be performed to move the project forward. This way, at any time, I can look at my list of next actions and just pick one.

- I have to timebox everything on my calendar. I have no classes to teach and only a handful of actual meetings, so 80-90% of my weekly calendar is open. I learned on sabbatical --- where I was also working with a lot of projects that had no fixed schedules --- to box off every minute of the working day into 30-, 60-, or 90-minute blocks that are single-mindedly devoted to working on just one project. This self-imposed schedule forces a focus on tasks in one thing for that one time block.

- Each project has to have a "definition of done". For example, "done" for the creativity task force means that we have a working prototype of an assessment for creativity and a rubric for grading it that we will try out in Modern Algebra later this semester. Far too often we academics engage in work without this clear "definition of done" --- we hold meetings with no agenda, teach classes with no learning objectives, start strategic initiatives with no sense of the desired outcomes --- and we get exactly what we plan for, which is nothing.

- The constraints on one's work have to come from a clear sense of purpose. Without knowing why I am doing something or what I hope to accomplish, there's no way to make use of naturally occuring constraints or to impose useful constraints of my own. Why am I working on central management of Chromebooks for example? Because students use the devices but we can't keep the machines up to date otherwise; it will help students learn better, and that's the primary reason I am in this business in the first place. Also, knowing what you should be doing serves as a filter for what you don't need to be doing. Knowing which tasks in my system are crucial for the January sprint allows me to be OK with postponing the others, as well as saying "no" to incoming work requests that don't serve the projects that are a priority. Without that filter, I'd have know basis for saying no to the right things.

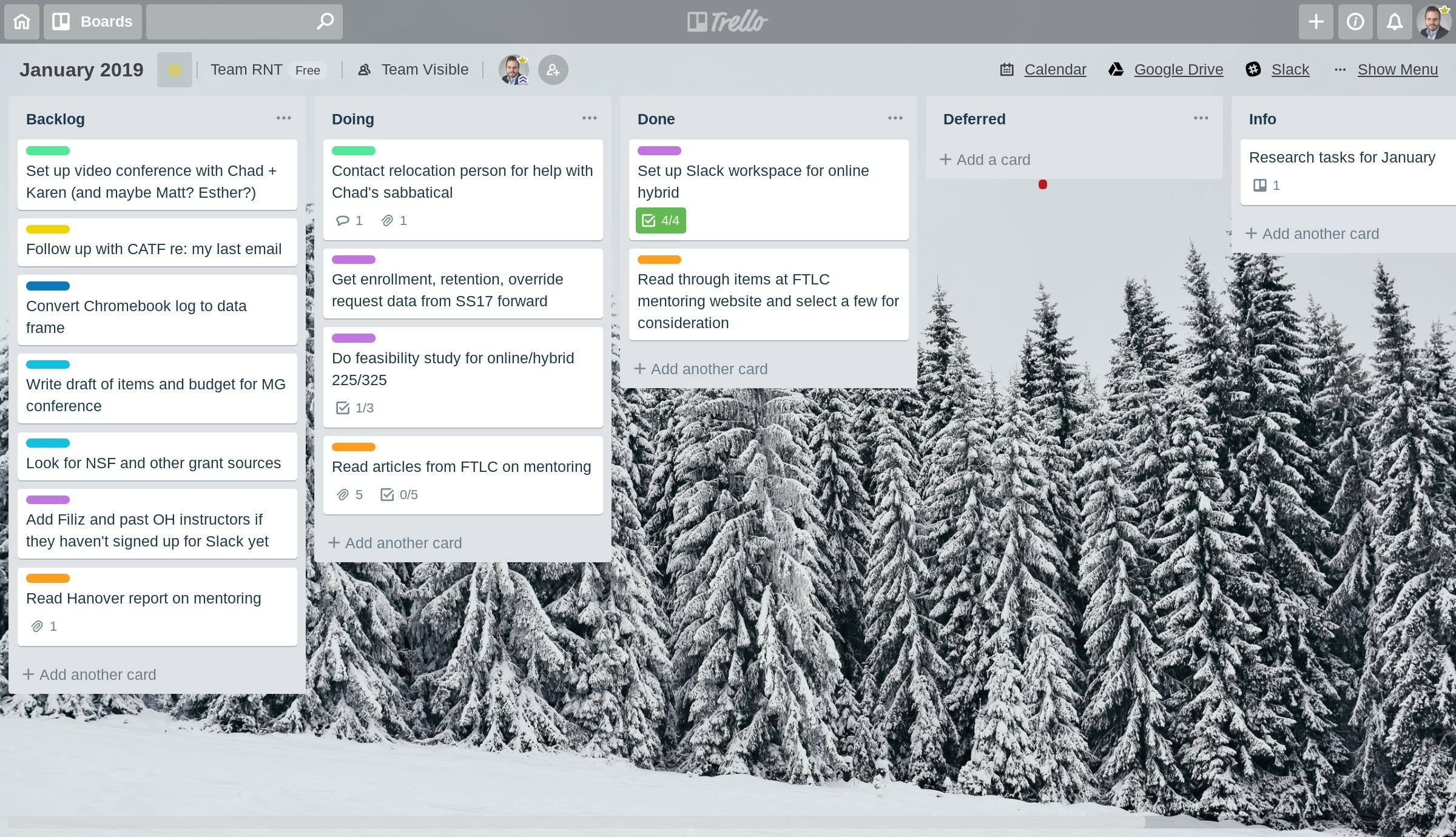

The urgency of doing this work in a one-month sprint also makes it important to have good tools for managing it all. I'm using two tools I use every day for this: Trello and ToDoist. I have a Trello board called "January 2019", set up as a simple kanban board. Each task or collection of related tasks is a card on the board in either the Backlog ("to get done"), Doing (underway), and Done columns.

The cards are dragged/dropped from one list to the next as they are completed. I also have "Deferred" in case any task enters a waiting period and "Info" for reference. When it's time to work, I keep the board open so I have a visual view of the status of all the parts of each of the projects. (This process is definitely heavily influenced by my sabbatical experience at Steelcase, where this Agile methodology was the way everything got done.)

I also wrote an applet on IFTTT that, whenever I add a new card to the January 2019 board (i.e. a new task or group of tasks to a project), it scrapes off the card title and adds it to my ToDoist inbox, which I can then sort into the correct project and tag it with time, context, and energy needed as well as make it the next action if appropriate. Whereas Trello gives me a visual view of my work, ToDoist is where I decide what's the best next action to perform in any given moment.

When I describe what I am doing to people, I often get the warning: Make sure you don't overdo it this month. Honestly, I don't feel harried or "overdone" at all. Having a clear sense of purpose, clear structure on what needs to be done, and also the knowledge of what doesn't need to get done right now or this month, makes all this feel like very little effort at all. It's actually really satisfying to be pushing the status bar on all these projects so far in such a short period of time. And you have to remember, the whole reason I'm doing this is because I am 100% determined to do no work whatsoever during my medical leave. [1] In order to do this guilt-free and stick to it, I need an efficient and energetic system to get things done.

And after all, isn't this the ideal state for work in academia --- to get our work done efficiently so that we get stuff done and then stop working at nights or on the weekends and spend that time without guilt on self-care, our families, and things we enjoy besides work? It makes me think that maybe we academics should think more often in terms of these intensive one-month sprints rather than languid 14-week terms.

This doesn't mean I won't be engaging my brain while on leave. For example I have a queue of books and articles to read, some DataCamp courses to take, and so on --- and I hope to keep blogging here about all that. That's fun, not work! ↩︎