Does alternative grading make cheating more likely?

This post first appeared at Grading For Growth on March 13.

Instructors are concerned about academic dishonesty like never before. First during the Big Pivot to online instruction in 2020 and continuing today with the rise of generative AI like ChatGPT, the opportunities to cheat have never been so readily available. And it's not just availability that's going up. Some reports note that while only 20% of students admitted to cheating in the 1940s, today the percentage may be as high as 80%1.

In today's environment, an instructor may ask whether alternative grading approaches make cheating more likely. If students are allowed reassessments, for example, does it open the door for dishonesty -- especially if the reassessments are coupled with flexible turn-in or deadline policies, or done outside of class time? And wouldn't timed tests, done at a single point in time under the direct supervision of the instructor, make cheating less likely to happen?

These kinds of questions that address the relationship of course design and structure and the likelihood of academic dishonesty, are the subject of this brief and useful paper, which we'll unpack today:

Anderman, E. M., & Koenka, A. C. (2017). The Relation Between Academic Motivation and Cheating. Theory Into Practice, 56(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1308172

(Unfortunately there doesn't appear to be a non-paywalled version of this article, but if you find one, leave a comment.)

What is this paper about?

This paper is in a journal called Theory into Practice, which should give you some idea of what it's about. The first half is a brief survey of years of research literature on academic motivation and academic dishonesty. The second half links this research to course design steps that instructors can take to put the research findings into practice.

The article doesn't focus on grading per se, although as you will see and can probably guess, grades and how we handle them play a central role in the recommendations the authors ultimately make. Instead, the main focus is on motivation. The authors note that students tend to ask themselves three questions when deciding whether or not to cheat on an assignment:

- What is my purpose? That is, what are my goals in doing this task that I am considering cheating on? Do I just want a good grade? Am I really trying to learn the material? Am I trying not to look stupid? Am I trying to be at the top of the class (or trying not to be at the bottom)?

- Can I do this? That is, do I have the necessary skills to complete the task? The authors note that the answer to this question is rooted in students' self-efficacy (their beliefs about their own abilities) and their expectations (what they and others believe is expected for success).

- What are the costs? What is the likelihood of getting caught? What are the explicit penalties if I am caught (grade reduction, expulsion, etc.)? What are the implicit penalties (guilt, embarrassment, diminished self-image, etc.)?

In my own experience both as a student and an instructor, this cost-benefit analysis flashes through one's mind on almost every assignment, even if you don't intend to cheat on it. The way these questions are answered determines whether a student cheats, and they can all be answered through the lens of motivation. Specifically, the authors use the concept of achievement goal orientation to frame the connections.

Drew Lewis wrote a guest article last year that went into depth on achievement goal orientation and its connection to grading systems. Go read the whole thing, but here is a recap.

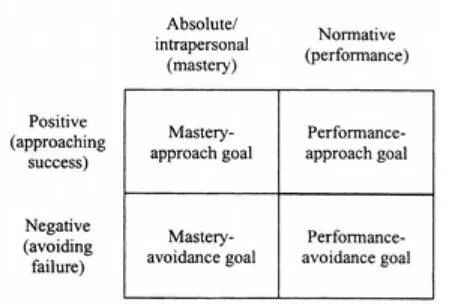

There are two major axes on which we can think about how students approach an academic task: Their motivations, which range between mastery (the desire to do well on or learn a task) and performance (the desire to perform well relative to others); and their direction of approach, either approaching success or avoiding failure. You can plot the combinations of these two axes2:

The authors of our present paper add a fifth category of motivation, extrinsic goals. This is the same notion as found in the self-determination theory of Deci and Ryan3: it's motivation based on an external reward -- like a grade.

Importantly, the authors here point out that a student's goals are partially based on their own beliefs, but they are also heavily influenced by what they think the teacher's goals are. A student with strong mastery-approach motivation who is in a course where the importance of getting good grades is stressed over and over again, may not want to cheat on an exam but might do it anyway because of the pressure that the perceived "goal structure" of the course presents.

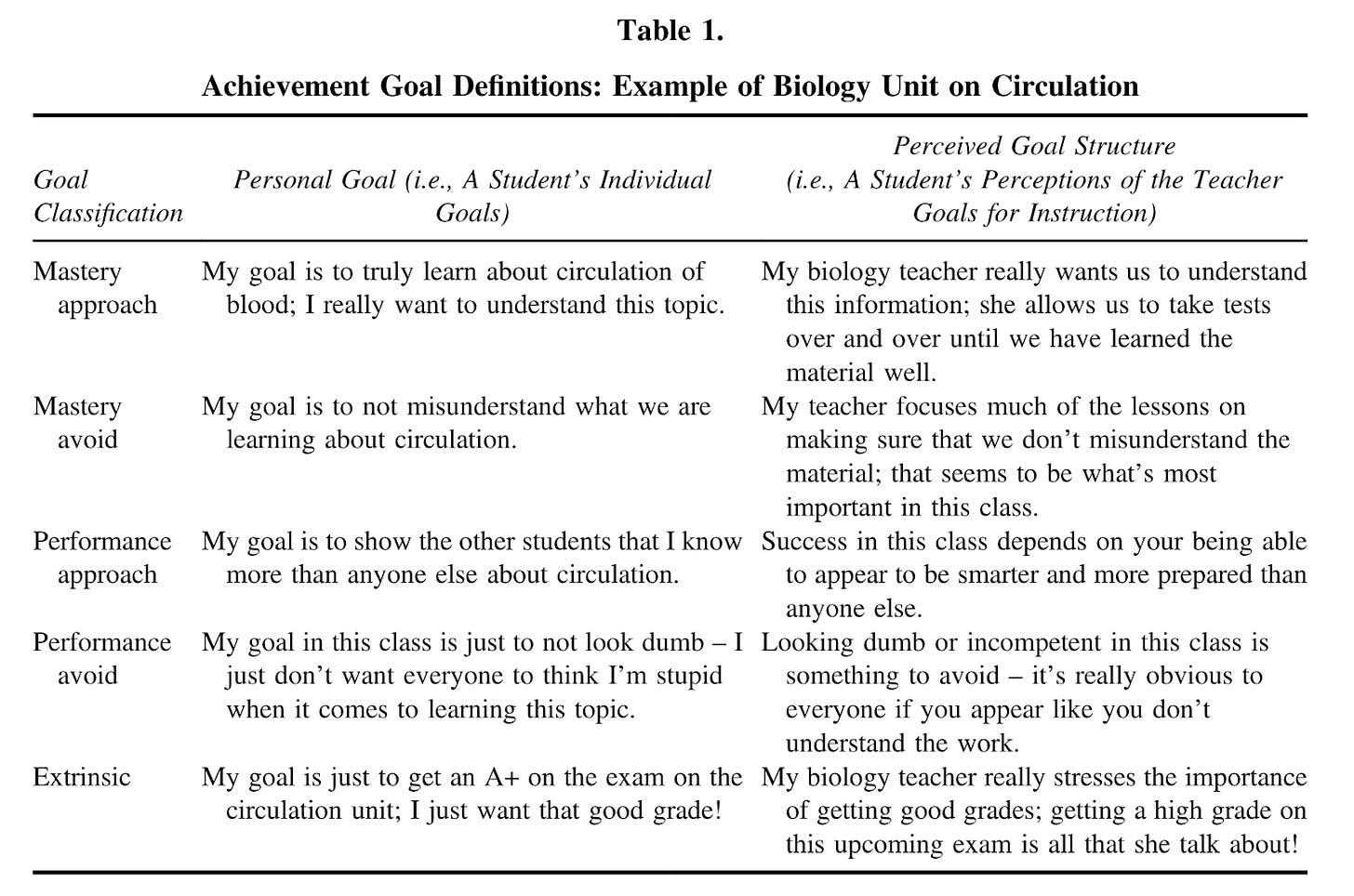

This table from the article is a useful catalog of how a student in a biology class might verbalize their own goals as well as the perceived goal structure of the course:

What did this paper find?

The authors connect their review of many years of research on goal orientation to cheating by addressing how different kinds of goal structures influence the way students might answer those three big questions we saw earlier.

What is my purpose? Perhaps the main point made in this paper is that students are less likely to cheat when they hold mastery goals, or perceive a mastery goal structure. Conversely, students are more likely to cheat when they hold extrinsic goals or perceive an extrinsic goal structure in the class. The authors also note that not much research exists on connections between performance-focused goals and cheating, although there is some evidence that cheating is related to performance-avoid goals (i.e. not wanting to look stupid).

Can I do this? There is generally an inverse relationship between perceived abilities on the one hand, and the rate of cheating on the other. This applies both to students' self-perception of skills as well as the belief that their efforts will end in failure. A student may cheat if they feel they don't have what it takes to complete the task honestly; but they also might cheat if they do think they can do the task but that, for example, the teacher may not grade them fairly. Furthermore, it's not necessarily the students who are struggling that will cheat. If a high-achieving student feels as though they cannot complete the task or that their efforts won't translate into success, they are just as likely to cheat as a low-achieving student.

What are the costs? There are no real surprises here: If a student believes that the risk of being caught cheating is lower than the benefit of getting away with it, that student will be more likely to cheat.

What does it all mean?

So, how might we change the equation about the costs and benefits of cheating? This is where the authors give useful practical advice, which I will sum up here in four basic categories.

First: Emphasize mastery. We should encourage students to go beyond surface measures and really master the material they are learning; and our course structures should reinforce this and support students’ efforts. Having both a mastery-approach goal orientation and a learning environment that stresses mastery as a goal, is the ideal and should greatly reduce cheating by greatly reducing the benefit one gains from cheating.

Second: De-emphasize grades. This doesn't necessarily mean "use ungrading"; in many situations grades may still be useful constructs to support student learning. Rather, it means we can take steps to take grades out of the center of the class. For example, don't talk about them so much; and don't communicate, either explicitly or implicitly, that grades are the most important thing in the class, or even that they are very important. By making grades less of an issue in a course, extrinsic goal motivation is removed from the picture.

Third, clearly communicate expectations. Many students cheat simply because they don't know what constitutes success on a task. Detailed rubrics can help by helping students develop "low outcome expectancies", that is, the view that negative consequences for poor performance won't be as bad as they might otherwise have anticipated. And grading according to a rubric and not through norm-referenced means (like grading on a curve) reduces the likelihood of cheating based on performance-approach goals.

Fourth, build students' self-efficacy. We saw above that one's belief about their abilities to perform a task has a strong effect on their likelihood of cheating. So it makes sense to take steps in class to build not only mastery of the material, but also students' beliefs about their own mastery, as well as to build the course so that actions that improve self-efficacy are themselves rewarded. (More on that below.)

How this connects to alternative grading

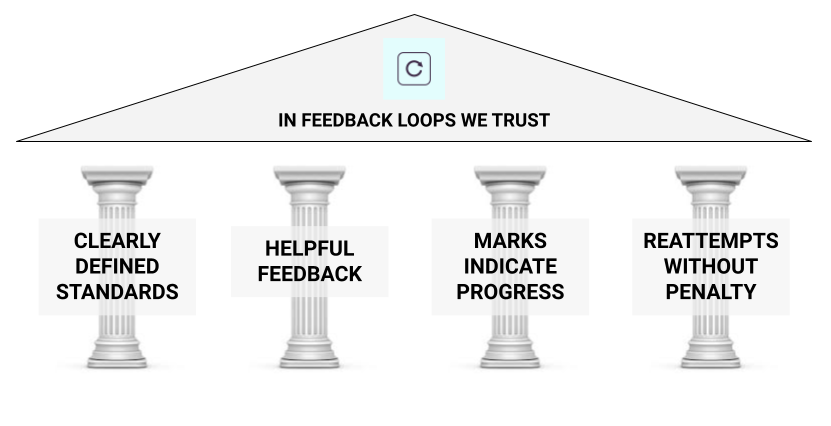

We've referenced the "Four Pillars" framework for alternative grading countless times here at this blog:

While no system of grading is 100% certain to eliminate cheating, based on today's paper we can definitely make the case that alternative grading approaches should reduce academic dishonesty relative to traditional points-based grading:

- Having clearly defined standards for what constitutes success on an academic task is the same thing as "clearly communicating expectations" suggested by the authors. Clearly defined standards also support mastery by explicitly stating what mastery looks like, which should make it easier to conceptualize for students.

- Giving helpful feedback is crucial for building both mastery and self-efficacy. Informative feedback, given in a professional manner with a view toward engagement in a feedback loop, lets students see not only what they have done wrong but also what they did right, and it invites them to improve -- which implicitly tells them not only that they can improve, but that you as the instructor both. believe that they can improve and expect them to improve.

- Marks that indicate progress can de-emphasize grades by taking all of the bogus pseudo-statistics of points and averages out of the game. They are also in some ways the flip-side of clearly defined standards, in that they clearly communicate the work done relative to the standard applied, and only in terms of the standard.

- Reattempts without penalty is the place where many skeptics point as a backdoor for cheating. But in fact, it's the most important piece of the puzzle in reducing academic dishonesty because it's where mastery really comes to life. When a student engages in the feedback loop opened by reattempts and reassessments, mastery is not only possible, it's all but certain, as long as students get helpful feedback and keep engaging with the loop. In fact, the authors (who do not have any particular preference for, or background in alternative grading methods) state (my emphases):

Formative assessments are inherently more mastery-focused, but it is still possible and important to emphasize mastery in summative contexts. For example, provide students with opportunities to remediate and possibly retake exams or rewrite assignments to improve. This clearly creates more work for teachers, but it sends an unambiguous message to students that the goal in the classroom is mastery of content; if students can redo their work until they attain mastery, cheating does not serve a purpose.

No instructor wants academic dishonesty in their class. We can try to prevent cheating through assessments done in a lockdown scenario coupled with police-state-like surveillance methods, but these are not only known to be ineffective, they only address the proximate causes of cheating. Alternative grading methods that follow the Four Pillars model, by contrast, address the ultimate causes. They are not only less prone to academic dishonesty than traditional methods, they are also more in tune with what, in my experience, students really want: To learn and to grow.