A new framework for active learning

Last week I mentioned a new paper by a group headed by Doug Lombardi, that proposed a new definition of active learning. The paper is:

Lombardi, D., Shipley, T. F., & Astronomy Team, Biology Team, Chemistry Team, Engineering Team, Geography Team, Geoscience Team, and Physics Team. (2021). The curious construct of active learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 22(1), 8-43.

It's open-access, and you can download it here.

UPDATE: It turns out that this is not open-access! But, for now at least, there's a publicly-available copy at this link.

A lot of people don't even realize there are operational definitions of active learning out there, but just assume that it's an undefined term that means "anything other than straight lecture". This perception isn't totally wrong. "Active learning" as a construct doesn't have a single, well-understood definition that can, for example, be reliably used in research or in interpreting existing research. Most of the time we focus more on instances of active learning than active learning as a whole: peer instruction, or team-based learning, or think-pair-share, and so on.

The one definition that seems to be used more than the others --- which I've used as the starting point for much of my writing, speaking, and workships --- is from Bonwell and Eison:

To provide a working definition for the following analysis, the authors propose that, given these characteristics and in the context of the college classroom, active learning be defined as anything that "involves students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing". (p. 19)

While that definition has unexpected depth (for example, the word "involves" has several layers of meaning), it's also almost too broad to be useful. For example when we see the classic Freeman PNAS study whose title states that Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics, there might be more questions than answers. What forms of active learning? Which students? Those questions are partially answered in the Freeman paper, but still, a superficial reading of the work can lead a person to think that any active learning will provide benefits to any student in that context, and that may not be the case.

That's where Doug Lombardi's team comes in. Looking through the literature on active learning, they identified two common denominators to the various instances of "active learning":

- Students have control of their learning "through some level of metacognitive sense making, self-assessment, and reflection"; and

- Active learning is "nested within the two familiar pedagogical approaches of student-centered and inquiry-based learning".

This is a helpful expansion of Bonwell and Eison. The first bullet echoes their inclusion of metacognition. The second clears up what kinds of "things" learners should be "doing" --- namely, things that are student-centered, and things that center on inquiry. I've talked to some instructors who are resistant to exploring active learning, who say "My students take a lot of notes during my lectures and do homework, isn't that active learning?" While there is possibly value in those things, Lombardi's framework would say those are not active learning activities.

Going through the literature on active learning in the STEM disciplines and pulling together the various threads of active learning found there, the paper proposes this definition of active learning which I find both helpful and interesting:

Active learning is a classroom situation in which the instructor and instructional activities explicitly afford students agency for their learning.

To unpack this a little:

- Active learning is defined as a "classroom situation". This is distinct from, say, an informal group study session or one-on-one work during office hours. A lot of quality learning can take place in either of those settings, but we distinguish "active learning" from these. I also interpret the word "classroom" to mean not necessarily a physical classroom space in a building, but any "space" --- including virtual spaces --- where these formal, planned situations happen. That can mean physical classrooms, but also Zoom breakout rooms or even asynchronous discussion boards. Active learning can and very often does take place in an online or hybrid setting.

- The pivotal word here is "agency". Quoting Albert Bandura, the Lombardi paper defines being an agent as "intentionally making things happen by one's actions". Agency is the essence of involvement in the earlier definition. It's the idea of control, with a dose of self-regulation. Being "involved" literally means being "folded into" --- being an inextricable part of the thing in which you're involved, in this case the learning process. It's way more than just listening to a lecture, or even taking notes on what you are hearing, or doing homework. Students can have agency for their learning in those activities; but it's not the default, and in my experience it usually doesn't happen consistently.

- The instructor matters and the course design matters. Who or what enables the agency we're talking about? Answer: the instructor does, and the learning activities do. Student agency doesn't just "happen" spontaneously. It's the result of intentional design choices by the instructor. I'm not suggesting that learning can be reduced to an engineering problem. But most certainly an instructor --- you and I --- can build learning environments where student agency is easy, as well as those where it's nearly impossible.

Side note on that last point: That's why I continue to hold that crafting clear, measurable learning objectives for courses is the first step for significant learning experiences. The learning process itself may be messy and resistant to being discretized. But starting with a framework is not the same as paint-by-numbers.

Lombardi's team not only gives us this interesting new definition, they also give us a framework for thinking about active learning. In their view (and I agree), learning is all about constructing understanding. It sounds like edu-speak, but it's actually a simple idea: When you learn something (not just memorize), it involves coming to your own terms with what you are learning. It's irrefutable that 2 times 3 is 6. But people can understand this fact in different ways, and we do ourselves a favor in school by letting kids explore those different ways and letting them settle on a way that clicks, for them.

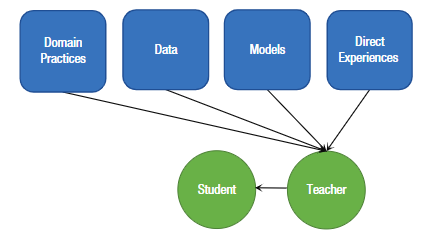

For Lombardi, traditional learning takes place in model where everything funnels through the teacher:

To me this is what lecturing, and sitting through a lecture, feels like. The learner --- although that term becomes tenuous in this situation --- has no direct contact with any of the ingredients of learning. They are being fed, as it were, by the teacher through whom all of those ingredients flow. Continuing with that analogy, it's like going to a restaurant. I eventually get a meal, but it's all funneling through the cooks (and the servers).

This is fine if all I am trying to do is fill my belly. But if I am trying to learn how to cook, to learn how to be a lifelong self-regulating food consumer capable of acting on my own without reliance on a third party --- it's a lousy model.

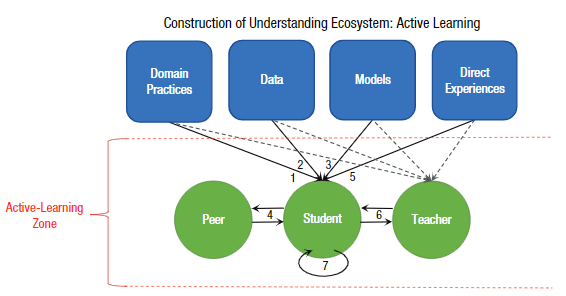

Lombardi proposes an alternative model, called the construction of understanding ecosystem:

To unpack this a little:

- It's a lot more complicated and "messy" than traditional learning. But it should be obvious that real learning cannot just be reduced to hearing and taking notes.

- It's really an ecosystem. It involves the learner having direct contact with all the ingredients for learning, as well as contact with people who can provide perspective, as well as contact with oneself (the self-loop labelled "7") which is metacognition.

- The teacher still matters. The teacher hasn't lost contact with the ingredients. There's merely mutual contact with those now, and contact between the teacher and the learner.

Active learning takes place in this ecosystem and it looks like this ecosystem. And again, such an ecosystem generally doesn't just happen on its own, especially in our lecture-first model of higher education that still predominates today. Getting our classrooms to look like this on a consistent basis takes significant, intentional design work on our part.

I like this ecosystem model for two main reasons.

First, within that ecosystem, true active learning could still look like many different things, and there's room under the umbrella for experienced practitioners looking to do even more, as well as instructors raised on lecture but who want to start moving away from that model by doing something small.

Second, at the same time, it does demarcate a boundary that distinguishes the kind of active learning we typically mean, from other forms of instruction that were questionable before (like doing homework in groups). That makes it useful for research on active learning, and I hope that in the next few years to come, we'll see more high-quality research with this model as its framework.