Working in context

Former Google and Yahoo! executive Marissa Mayer has a saying: Creativity loves constraint.

Not only does creativity love constraint, productivity requires it, especially among academic folks. The story of the pandemic year, for many of us faculty, was a workload that quickly overran our buffers and wreaked havoc on our work and personal lives. It was all unconstrained. And if we're being honest with ourselves, many times we don't do much to constrain it. Stuff comes in, and we leave it in email or put it on a to-do list (or pretend that the email inbox is the to-do list) and because all that stuff is never rounded up and put in its place, it takes over like an invasive species. We spend time and energy worrying about tasks that we cannot possibly do in the moment, or we expend energy hopping back and forth between tasks that aren't related.

This week we're going to work on that.

Today we're one month into the Summer Challenge, and if you've been following it, you should be feeling much more in control of all this stuff and much more like you are telling your stuff what to do, rather than the other way around. You've learned to capture what comes in and then clarify its meaning — getting the non-actionable stuff out of the way, doing the low-hanging stuff immediately, and organizing the rest into calendar items, projects with a clearly defined next action, and items that should be done by others. But there's one part of this process that might feel like the elephant in the room: the Next Actions list.

As you've learned, the Next Actions list is the list of all your items that are actionable, are single actions and not projects, require more than two minutes to complete, are owned by you, and don't have external deadlines. There is a strong chance that this list is huge. Where do you start, and how is the Next Actions list any better than the old-and-busted to-do lists that you never completed in the first place?

The concept of Contexts

Looking at your Next Actions list, you probably notice a couple of things about its contents. First, there are some things that can't be done except under specific conditions. For example, if you need to fix your kitchen sink, you can't do that when you are away from home; if you need to order something online, you can't do that when you're on an airplane with no wifi. On the flip side, there are some tasks that all require the same conditions and are most efficiently done when batched together. Phone calls are a really good example. I hate talking on the phone, so when I have phone calls to make, it's much better when I can just knock all of them out in a single sitting. If I have errands to run, it's a much better use of my time to run all the errands in one trip rather than separate runs for each errand.

This notion of the conditions under which stuff can be done, and letting the conditions serve as a constraint for guiding our actions, gets us to the idea of contexts.

In Getting Things Done, David Allen sets up this idea as follows:

Over many years I have discovered that the best way to be reminded of an "as soon as I can" action is by the particular context required for that action — that is, either the tool or the location or the situation needed to complete it. For instance, if the action requires a computer, it should go on an At Computer list. If your action demands that you be out and moving around in the world (such as stopping by the bank or going to the hardware store), the Errands list would be the appropriate place to track it. (p. 146)

What's being implied here is a further breakdown of the Next Actions lists into sublists, or rather separate lists, all based on the conditions that are required for the action. Those conditions — based on tools available, location, and situation — are constraints, that we call contexts. In the GTD book, Allen lists some common contexts: Calls, At Computer, Errands, At Office, At Home, Anywhere, Agendas, and Read/Review.

So that's this week's challenge: Take your Next Actions list and partition it into contexts, according to the tools, locations, and situations that you frequently need.

How I use contexts

I did not use contexts for a long time. They seemed like an unnecessary complication. After all, when 90% of my Next Actions require a computer, is there any point to an "At Computer" list? And in the era of pandemic lockdowns, are the "At Office" and "At Home" contexts really different? So I kept all my next actions in a single large list.

But then at some point in the last 2-3 years, I started using Trello to manage my lists. The David Allen Company produces an official guide to using Trello, and in it, they recommend using a board for next actions, separated into lists for each context. I thought this was weird and unnatural, and I resisted it. But then I tried it out, and I began to see the wisdom in this approach.

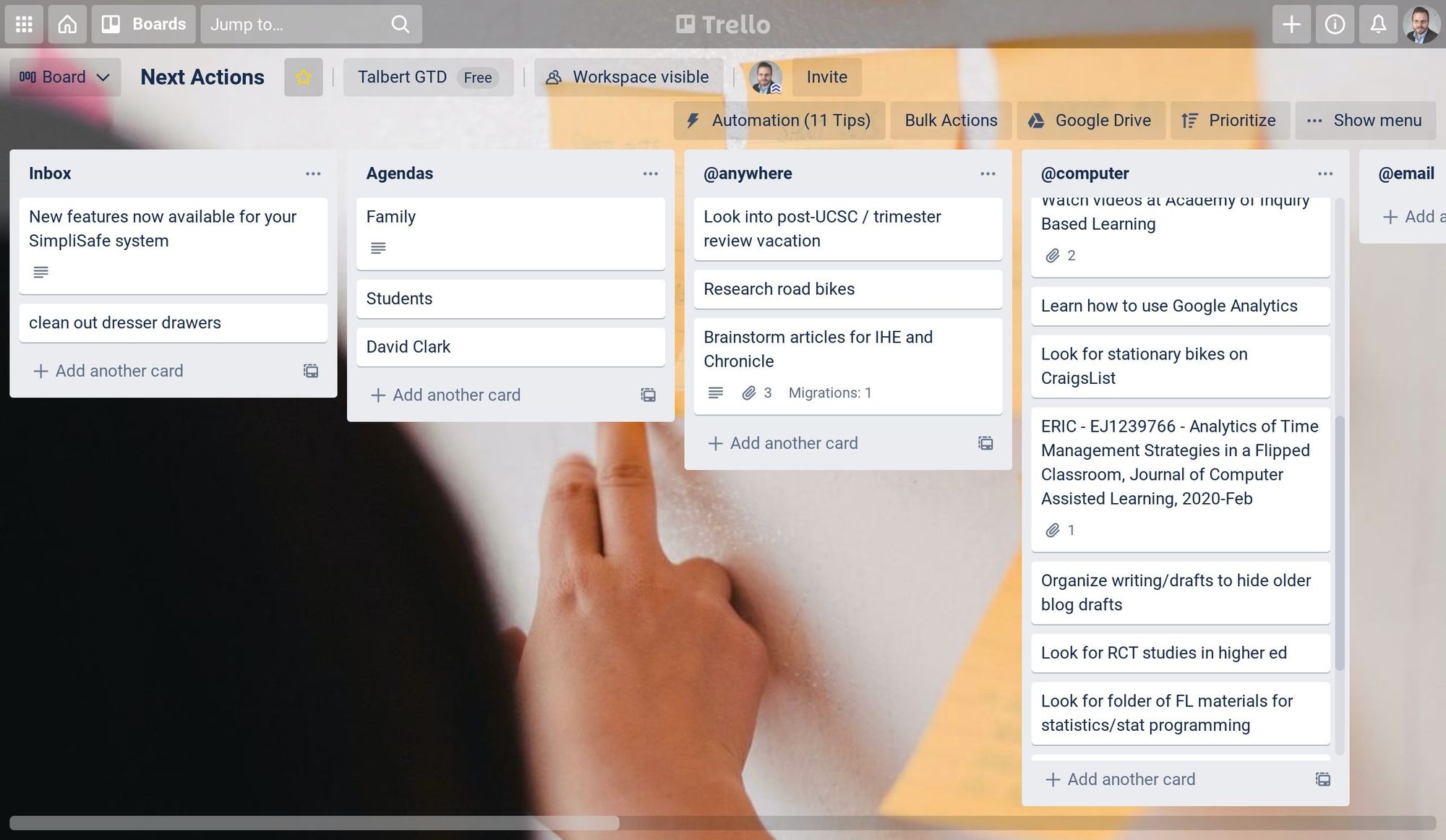

The contexts that I use are Agendas, Anywhere, Computer, Email, Home, Errands, Phone, and GVSU (for stuff that can only be done on my university's campus). During the school year I often add another context, Grading, since I view grading as a particular "location" in terms of a state of mind that's separate from everything else. I track my Next Actions in Trello, where I have a board for Next Actions and a list for each context. It's too wide to be viewed in one screen, but here's a portion of it:

The "Inbox" list is just a temporary holding spot for incoming stuff; I can forward emails directly into this list, and I have an action set up on Google Assistant where I can add things to this list using voice commands via my phone, Chromebook, or Google Home. Each task is a card. When I go through the Clarify process, I just drag the card to its context list.

These contexts have evolved over time, and others might use different buckets for theirs. Over the years, I have mostly tried to winnow things down to a small collection of contexts that I actually use. For example, instead of Computer I used to have several lists for specific computer situations — one for when I had a computer but was offline, another for tasks that could only be done on my Windows laptop, etc. But this was just too much maintenance, so I collapsed it all back into a single (large and possibly oversimplified) Computer list.

Some folks like to add contexts that aren't related to tools, location, or situation — such as energy level or time required. This can be useful. For example if you're using an app like ToDoist, contexts can be done with tags that allow you to set up a filter for something like "All tasks that can be done at the office if I have 10 minutes or less and my energy level is high". I used to set things up this way myself. While there's value in this, I found that once I was within a tools/location/situation context, my brain is better than a computer at doing any further sorting. Better to keep things simple and avoid one-to-many relationships between tasks and contexts, in my view.

The two rules for using contexts

To actually use contexts, there are two simple rules:

- Give zero attention to tasks or lists that are out of context.

- Avoid switching contexts.

The first rule means that I should not even be thinking about, much less looking at, tasks that don't match up with the context I'm in. If I'm not on campus, the GVSU list should be completely out of sight/out of mind. If I'm away from home, I should not even be thinking about the Home list. If I did give attention to out-of-context tasks, all it would do is distract me from the things that I can do.

In fact, ideally I should only have one list at a time in my conscious mind, namely the list that best fits my tools available, location, and situation. In practice, that's not really how it works; right now for example I am home and at my computer, so while I should not be giving any attention to the GVSU or Errands lists, I could technically give attention to both the Home and Computer lists. The main thing is to pay no mind to tasks that are impossible due to constraints on your context.

The second rule is about batching tasks together. Since I am currently both at home and on the computer, I could finish writing this post (Computer) and then go mow the back yard (Home), then come back and write the letter of recommendation I agreed to do for a colleague (Computer again). But it would make more sense, and be more efficient use of time, if I did the two Computer tasks back to back, then switch contexts and mow the lawn.

You can't totally avoid switching contexts, but you can minimize it, and study after study tells us that context-switching is bad for us in many ways and ought to be minimized. I have a suspicion that a large portion of the existential exhaustion that many faculty members experienced in 2019-2020 was due to relentless, unchecked context switching. It's what happens when you have stuff coming in constantly without imposing some order on it. Every inbox item sounds like it's the most urgent thing ever, but the simple fact is that if I'm asked to do or think about something and I'm not in the right location, or don't have the tools needed, or in another situation that precludes it, it's going to have to wait.

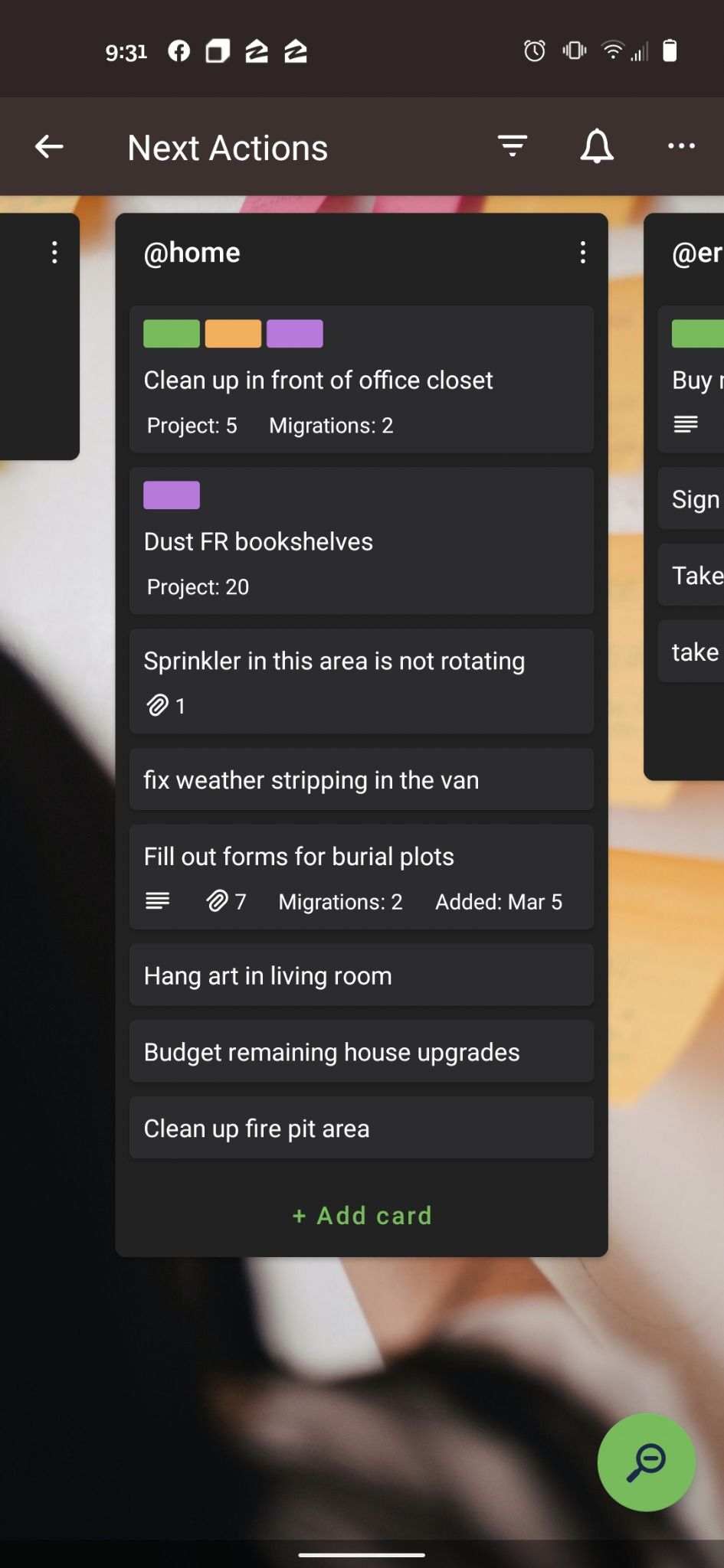

So when I am working, I typically open Trello and focus in on just one list that is within context. A happy accident of the Trello mobile app is that the screen on my phone is narrow enough that only one list at a time ever appears, so it helps me focus:

This could just as easily be done in other apps, or using no apps at all. For example you could use a Google Doc or plain text file for next actions with headings to separate the contexts, or separate files for each context. Or if you're a bullet journalist, your notebook can include a spread for each context, and you would just keep your journal open to whatever spread makes sense in the moment. This analog approach, in fact, is David Allen's original formulation of the GTD methodology, when it was only David Allen using it. He would put all his next actions on 3x5 index cards, one card per context — and look only at the one card that best fit the context, and physically put away all the others.

The Challenge

This week:

- Continue practicing ubiquitous capture;

- Continue to go through the Clarify loop to process what you capture;

- But this week, determine a collection of contexts that make sense for you and split up your Next Actions list into those contexts. Partition your next actions into contexts and operate out of only one context list at a time.

Don't overthink the contexts. Keep things simple, and if you're not sure which context a task belongs in, just make a snap decision using your best judgment. You can fix it later if you want.