Lessons about socially-distanced active learning from a classroom redesign

This semester I've been teaching face-to-face with some subset of my students for for 10 hours per week. Even without thinking about potential health concerns from Covid-19, this has been a challenge. But I have to say that it's been much less so than I, and many others, thought it would be back in the spring and summer. The conversations four or five months ago were about whether teaching face-to-face in a socially distanced classroom was even going to be possible. But like so many things about Fall 2020, the challenges of teaching F2F in this environment, while real, didn't amount to nearly as much as we thought they would.

When I was thinking about how I'd teach in my classroom spaces this summer, I thought a lot about this paper which I studied during my sabbatical with Steelcase:

Henshaw, R. G., Edwards, P. M., & Bagley, E. J. (2011). Use of Swivel Desks and Aisle Space to Promote Interaction in Mid-Sized College Classrooms. Journal of Learning Spaces, 1(1), n1.

Having been written in 2011, though, this paper obviously did not address anything about the need to design learning spaces for use in a socially distanced environment, so I've also been wondering about the validity of this paper's research in our present, and probably future, situation.

What this study is about

In this study, the authors wanted to see if a small but significant change in the furniture design of a medium-sized classroom space could facilitate better interaction and engagement among students. The "medium-sized" spaces were in the 25-50 student range typically arranged as lecture halls, all facing forward to a clearly-defined "front" of the room in a 6x8 grid.

As Anat Mor-Avi and I pointed out in our literature review on active learning spaces, there are numerous issues with this style of classroom space, with two rising to the top: First, the default layout is optimized for passive learning and lecture, rather than active learning. While it's possible to do active learning in such a room, it's not the default; students and faculty essentially have to hack the architecture of the room to do active learning. Second, the design of the room sets up a cultural expectation for instruction that is just as much of a barrier as anything physical. When you walk into a room like this, you subconsciously adopt an expectation for what's going to happen in that room pedagogically: There's a clear "front" to the room, and it's going to be occupied by a lecturer; and you are going to sit still, face forward, and listen. Anything else transgresses those cultural norms and triggers a fight-or-flight response among the students (and probably the professor too).

To break out of these barriers to active learning, redesigning the class space is essential. But what's the best way to do that? When Anat and I did our research, we found that there's no one-size-fits-all "best" solution to that problem, but there are a few simple underlying principles that yield results. Flexibility is the main one, meaning that since students learn differently and active learning can take on so many forms, the room should be reconfigurable to fit the audience, the learning objectives, and the moment during instruction. Flow was another, by which we mean not only the flow of air, light, and traffic through the room but also the flow of information, for example by having easy access to projection, computers, and whiteboards. And finally connection is important, whereby it's easy for students and instructors to get with each other, communicate, and share ideas.

Back to the study. The authors point out that, contrary to the usual solution of putting wheels on chairs and desks, having movable furniture in a classroom actually prevents some instructors from using active learning more:

Classroom support staff at this university report that at the beginning of a term it is common to see instructors reconfigure the room before class begins. Eventually most of them tire of taking the time to rearrange furniture and accept the prevailing seat arrangement. In fact, all of the instructors in the current study reported at least occasionally moving classroom furniture for learning activities and all also reported that the layout of traditional rooms has discouraged the use of particular teaching techniques.

I have a number of questions about this claim, which I'll share at the end. But the main message is that even if it's easy to rearrange furniture, the fact that it has to be done at all mitigates against doing it. Again, people default to the default.

How the study was designed

So in the study, a single 48-student room at Iowa State was outfitted not with chairs on wheels but swivel chairs that were bolted to the floor — so no overhead required for moving furniture around, because it wasn't possible — but which allowed students to turn around 360 degrees in their seats with almost no effort. The seats were manufactured by Krueger International (KI) and while I couldn't find any current product information on these, here's a similar product made for little kids (which are actually movable and stackable — the chairs that is, not the kids), and this photo from the paper shows a little of what the modified room looked like (direct link):

The 48-student room was split into four zones of 3x4 grids, with a big space at the front (again, I have some questions here) with large projection screens and, importantly, two large aisles cutting across the horizontal and vertical axes of the room, which you can see in the photo. The students could easily pivot to connect with other students, and the instructor could easily move out and get with any student in the room via the two large aisles.

The study itself is qualitative. Surveys were given out to students and instructors using the room regarding how the room was used, how active learning was helped or hindered by the modified room and by past classroom spaces, and generally about student engagement. There were also video observations done of instruction in the room to try to discern patterns for how students used the seats and how instructors moved through the spaces.

What the study found

Instructors reported that the swivel seats boosted the interactivity of the class — in fact some complained about this, that students would "swing around to chatter" even when active learning was not taking place. (The more things change, etc.) Similarly, 94% of the students indicated that the room design helped improve the quality of their interactions with other students, with over 1/4 of the students specifically mentioning "eye contact or the ability to look at others" as a positive benefit.

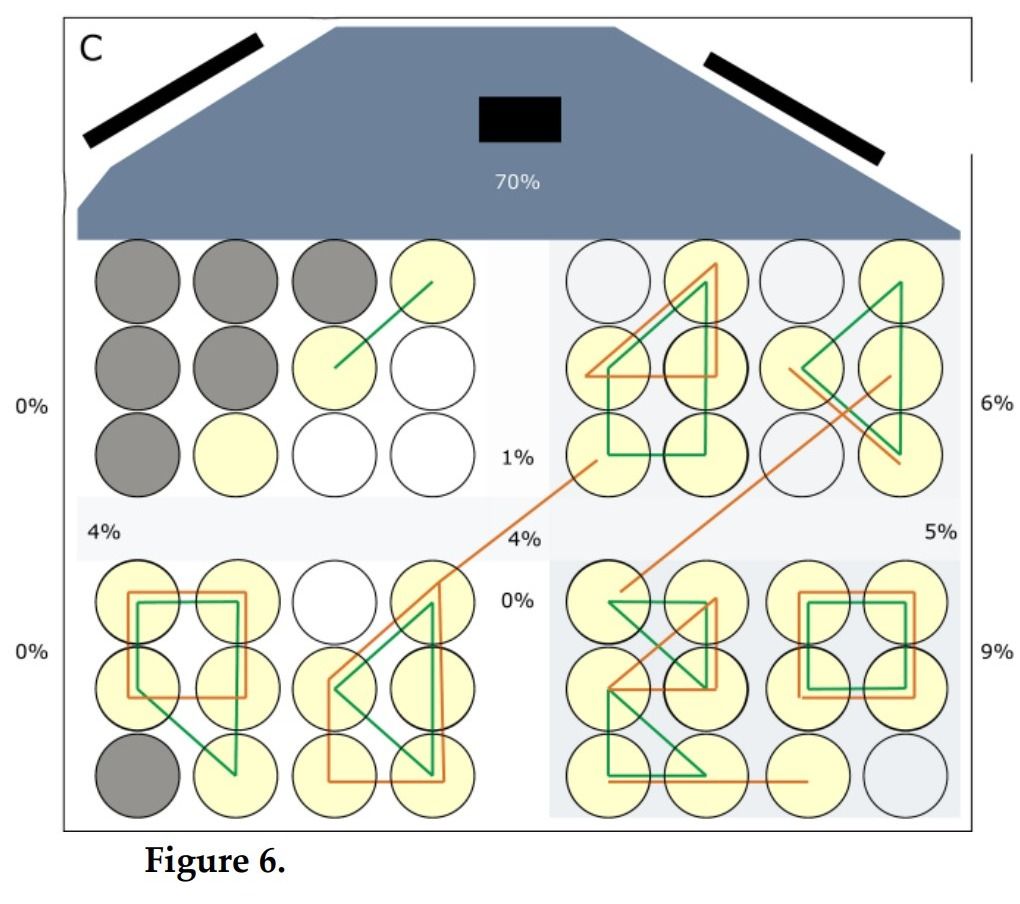

Some interesting patterns of use of the seats emerged from the video observations. Being in a 3x4 grid, students had the ability to group together spontaneously in a variety of geometric configurations — or not group together at all, or interact across groups and between different 3x4 grids. Here's one diagram of use from a specific class meeting. The green lines indicate distinct groups and the orange lines interactions between groups (direct link):

Having the two large aisles allowed instructors to get off the stage and circulate among students, and most instructors did so with a higher frequency than they normally would. The diagram above for example indicates that the instructor of that class spent only 70% of their time on stage, whereas that percentage would be close to 100% in a traditional room. Student engagement benefited from this, with several pointing out that they were "forced" to pay attention when the instructor was circulating and that there was "nowhere to hide".

Finally, instructors noted that it was much easier to transition between lecture and discussion modes in this classroom than in a traditional room, which one can take to mean that it's easier to adopt active learning practices in that space. So the barriers to using active learning were effectively lowered.

What this means for the rest of us

When it came time to get my Fall 2020 courses ready, I immediately thought of this paper and how simply allowing students to pivot 360 degrees in place is a workable strategy for active learning in a socially distanced classroom. Active learning is not the same thing as "group work" and, despite all I heard to the contrary, active learning can be done well when students need to remain 6 feet apart. (Indeed we must do active learning in these classrooms to honor the risks we are taking to have F2F instruction at all.) All we have to do is specify where students need to sit to maintain a safe environment, then let them turn around.

I found the comment from students about the importance of eye contact to be very interesting, given that we have to wear masks in class now. There was a lot of concern before Fall 2020 about losing the human touch if we have to be F2F in a classroom while masked. But it may turn out, since masks direct the attention to the eyes, that masking actually enhances the effects of learning. Eye contact is well known to stimulate cognitive development in young children as well as affective responses, and perhaps it does this too for college students. (Although, excessive eye contact can also be draining.)

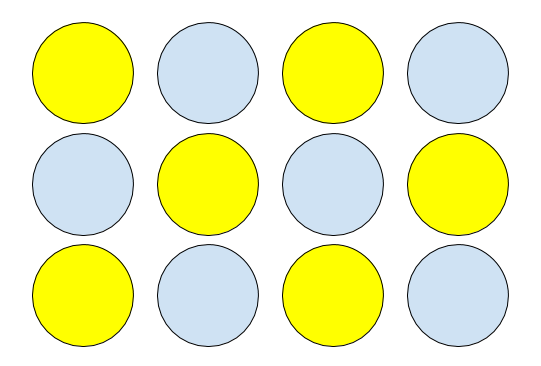

There are a few issues to mention. The first and most serious isn't with the study but with the adaptability of this room configuration for social distancing during Covid-19. According to one diagram in the paper, within each 3x4 grid of seats, each seat is 51 inches from its neighbor on the left and right and 45 inches from the neighbor in front. And we need 6 feet of separation between students. But since the seats don't move, you cannot have a configuration like this which would at least allow half the students to be present, using the yellow seats (direct link):

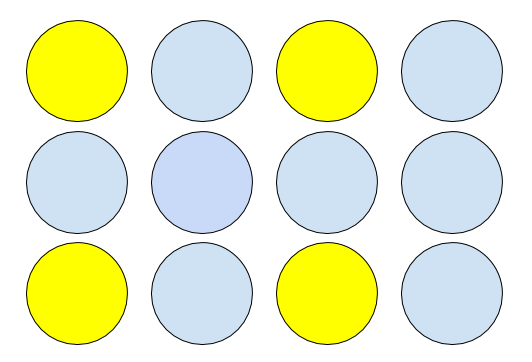

That's because the distance from the seat on a "corner" to the seat in the "middle" is 68 inches — close to the magic number of 72 inches but not enough. (Shout-out to the Pythagorean Theorem.) So, the best you could do is this configuration (direct link):

And that wipes out 2/3 of the seats in the room. As a former department chair, let me make clear, this is not good. And you're stuck with this because the chairs are bolted to the floor.

Another thing that wouldn't work in today's classroom, unfortunately, is having the two large aisles. This is a good idea in this study and it was effective for everyone, but social distancing puts a wall of separation between students and the instructor. This is something we should probably all do with our classroom design even if we do nothing else — as soon as we're all vaccinated.

I'm not sure why the authors here felt they are a better solution for the problem in this study than chairs on wheels like the Steelcase Node chair. Earlier I shared a quote from the paper that instructors found it tiresome to constantly rearrange furniture, but that seems spurious — why not just make the students do it, by putting a diagram of how you want the seats arranged and then saying "Go"? If the chairs and desks are on wheels, it's trivial.

Finally, not only would chairs on wheels be better to make social distancing work out and maximize the safe occupancy of the room, it would probably be no more expensive than putting down bolted swivel chairs. A base-model Node runs about USD 400-500 each, times 48 seats is under USD 24,000 before bulk pricing; the paper mentioned that it cost about USD 27,000 to renovate the classroom with swivel chairs (although this also included new computer and projection technology and possibly electrical etc. work).

So basically we should never bolt anything to the floors of our classrooms unless we are 100% certain we will never need to move them. And if Covid-19 has taught us anything, it's that we cannot be 100% certain about anything. I'm pretty sure the authors never factored in the need for social distancing in their designs; it's yet another reason why flexibility is so important in classroom spaces.

In sum, while the specifics of this study aren't something I'd recommend copying in our classrooms today, I would say that this study teaches us that anything we can do to improve flow, flexibiity, and connectedness in our classrooms is something we should look into. At the heart of this study is a good approach to active learning that hits all of those notes while requiring only that students turn around in place — that's a minimalism that can have all kinds of good effects.