Clarifying what you captured

As we saw in the previous post on the Summer Challenge, Capturing is the first step toward a more meaningful, relaxed, and in-control experience as an academic. If you practiced this habit in the past week, nothing noteworthy has escaped your attention: It's been captured, and it's not pulling on your attention like an impatient 4-year old. But we can't just put stuff in a tank --- the purpose of capturing is to review the stuff we've captured later. That's this week's habit: Clarifying.

I can't overstate how important this process is for being happy and in control as an academic. So many faculty (and students, administrators, etc.) default to the belief that every item that gets our attention needs to be acted upon ASAP. This just isn't true. But we often act like it, and you know what happens: Instant overwhelm. And if you treat every attention-grabbing item as actionable, it makes it a lot harder to know what you should be doing in the moment, and we usually work on only the things that are the "latest and loudest" and shortchange the things that are important --- things like exercise, study time, time for family, and more. In the Clarifying process, you'll be asking of each item that has your attention: What does it mean, to me? which puts you in control.

To begin, you'll need the following:

- All your inboxes where you captured things.

- Four lists, which you can keep on paper or in a computer file: Someday/Maybe, Projects, Agendas, and Next Actions.

- A folder (paper or digital) called Reference.

- A calendar (paper or digital).

We're going to loop through each item in each inbox and subject it to a series of questions that will clarify what the item means to us, and what to do with it next. There are only two rules to this game: (1) Don't skip items --- start from the top of your inbox and work your way down, and don't avoid any items that seem hard to work with; and (2) Don't put anything back into the inbox --- by the time you're done with this process, each item will be on one of the lists, in the Reference folder, on the calendar, or in the trash, but your inbox will be empty. Keep it that way.

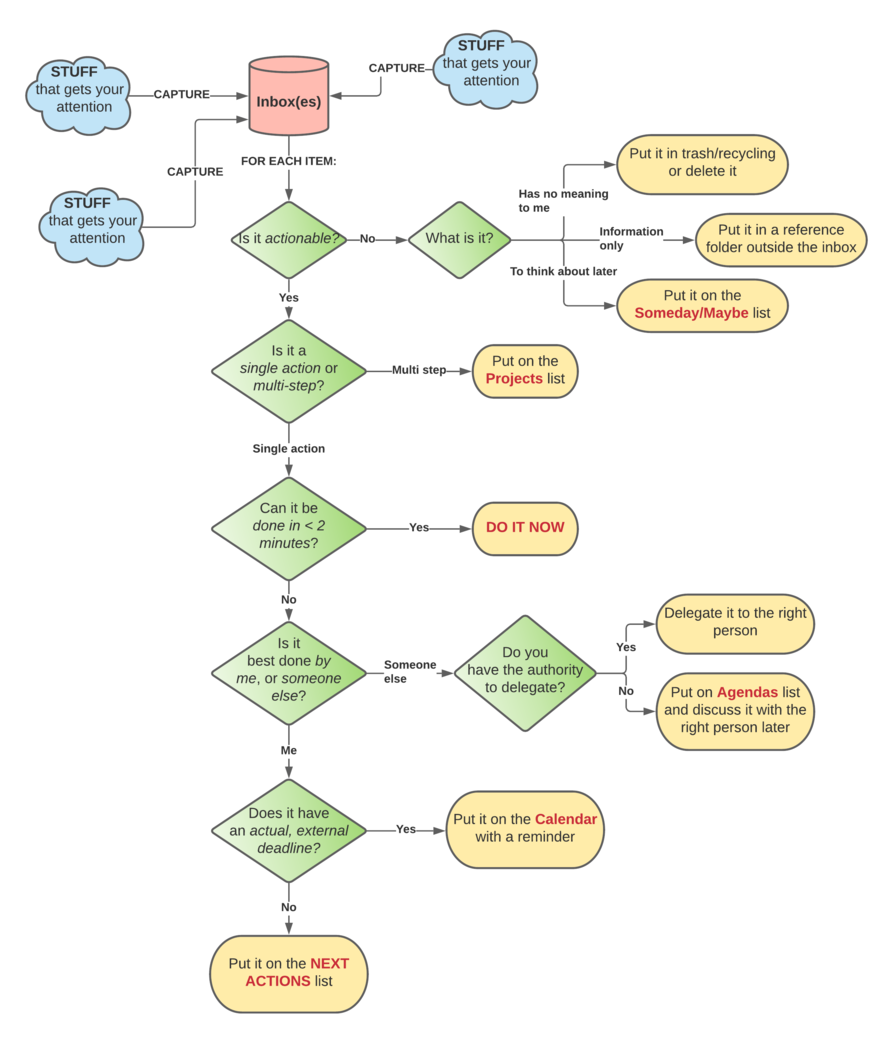

Clarifying is a process, and I've summarized the process in this flowchart, which is a modification of one found in David Allen's classic book on Getting Things Done:

Now we'll step through each part of the process in detail. First question for the item from your inbox:

Is it actionable?

Does this item require me to do anything about it at all? Surprisingly often, the answer is No, because it's one of three kinds of things:

- It's trash or spam. The item has no real meaning to you. This isn't a judgment on the item's merits, just a fact about its relationship to you. Spam emails are an obvious example; also items that don't pertain to you, like a grant announcement for an area you have no interest in, or most of the coupon packets you get in physical mail. Once you've determined the item is in this category, get rid of it. Just click "Delete" or "Archive", or throw the thing in the bin, and move on. (If you're worried you might need it later, then it's not trash, so go to the next item.).

- It's information only. The item contains information you might want to look up later, but doesn't require any action on your part. For example, a note from your department chair with an update about fall enrollments isn't trash, but it's not actionable either --- it's just useful info. (You might decide that it should be deleted after reading it, or archived for later; up to you.) If the item is information only, put it in the Reference file and out of the inbox. We'll discuss strategies for filing information away in a later post; for now we'll keep it simple and use a single monolithic Reference file for everything. You may need two, one for physical items and another for digital.

- It's not something to act on now, but maybe later or someday. There are a lot of items that, if we're honest, belong here --- they're interesting and you'd like to get to them at some point, but you don't have the bandwidth to do them now or in the near future. If the item is something you want to act on, but you don't seriously intend to do it now or soon, put it on the Someday/Maybe list. I find this is hard for a lot of academics. We're exposed to interesting opportunities and ideas all the time, and we're overachievers so we want to add each and every one of those to our to-do lists. But all this does is produce untenable to-do lists that never get done, which is demoralizing. The Someday/Maybe list is a middle ground between the to-do list and forgetting the thing entirely. Cool ideas and opportunities that you'll get to someday, maybe, live here.

This question is powerful. It filters out all the items that don't need to be acted upon right away from those that do. If you are honest with your clarifications, then you might find that the list of things you captured is dramatically smaller by this point. You might also feel a sudden ramp-up in focus and control. You are telling your stuff where it belongs, not the other way around.

If the item is actionable, there's more to ask.

Is it doable in just one action, or is it a multi-step process?

Not all actionable items are created equal. For example "Grade papers from 10:00am class" and "Reply to email from department chair" are two very different things: the former is a major undertaking that could take days, while the other is a one-time action that can be done in one stroke. The fact that one is a multi-step process and the other (typically) isn't, makes these two items fundamentally different, and this question separates them.

We'll adopt the language of Getting Things Done, and say that an item that needs to be done within one year and requires more than one action to complete is a project. For example, most of the time grading essays or papers is a project --- it's not a single thing that we do, but a bundle of actions that all need to be done in order for the project to be done. Replying to an email, on the other hand, is a single task (unless it's a really serious or convoluted email).

If you determine that the item in hand is a project (it needs to be done within a year and it takes more than one step to complete) then put it on the Projects list. In a later post, we'll discuss how to handle projects in this workflow. But for now, just park it on the Projects list.

Distinguishing between multi-step projects and single-step tasks is crucial for avoiding overwhelm as an academic. Consider this familiar situation: A faculty member is feeling ambitious and makes a to-do list for the day that includes "Reply to the department chair's email", "Pick up milk from the store", "Grade Test 2", and "Check on due date for grant proposal". Which one of these is unlike the others? The grading item is sitting there, sucking away your energy and attention. There are two likely outcomes: Do all the other, simpler tasks on the list and avoid the grading item; or devote all your energy to the grading item and have nothing left over for the other stuff. Either way, a large part of your to-do list goes undone, and this is shaming and demoralizing despite how we might joke about it. The problem is that you put a project where tasks are supposed to go, and we can't "do" projects like we do tasks. Eventually, what we have to do is handle projects separately by breaking them down into their component tasks and thinking about those separately. That's a habit we'll build later.

If the item isn't a project, then it's a single task, and we ask a very important question about it next:

Can it be completed in two minutes or less?

If the item can be completed in two minutes or less, then do it now.

This is known as the Two Minute Rule. If something has grabbed your attention, and it's a single action that can be resolved quickly, you don't put it on a to-do list --- you just do it, right then and there, and be done with it.

The liberating power of the Two Minute Rule is not to be underestimated. By practicing it, you kill off all the low-hanging fruit of what's getting your attention. That attention is then freed up to focus on other, more significant things. Practicing the Two Minute Rule does require some skill with estimating how long it takes to do things, and many times a "two minute job" for me has turned into an hour-long affair. But most of the time, we are at least pretty good at distinguishing quick things from not-quick things.

If the item can't be completed in two minutes or less, then we move on:

Is the item best done by me, or by someone else?

Sometimes you end up with an item that's actionable, is a single action, and takes longer than two minutes... but it's not actually for you.

Since we often shift roles in academia, this can happen frequently. For example, I was department chair in AY 2019-2020 but I get lots of email from people who think I'm still chair, with information or requests that I can't act upon, but the real chair can. I also get questions about technology from my math colleagues, but there's actually another person in the department with the title of "Instructional Resources Coordinator" whose job is to handle those.

If you determine that the item isn't best done by you, then determine who is the right person to handle it, and either delegate it or discuss it with them. Those emails from people who think I'm still chair get forwarded to the actual chair, for example (or to the administrative assistant, who triages them). Tech requests get forwarded to (or discussed with) the Instructional Resources Coordinator, or maybe Tech Support. Or, if I don't know who the right person is, I reply to the person asking the question and let them know. The idea is don't take on tasks that aren't for you, whether that's because there's someone else better suited for them or simply because it's not your responsibility.

This obviously requires some care, and involves navigating difficult issues about power and equity. Rather than make this post any longer, I'll write some specific thoughts on this in a separate post. For now, I'll just say: Most "delegation" in academia should look like negotiation, even if you have the authority to delegate --- and especially if you don't. If you are not in a position to delegate tasks, then don't just forward the task on to the right person; put their name on the Agendas list and discuss the task with them whenever you have the chance.

If the item you are reviewing is do be done by you, we move on:

Does it have a deadline?

By "deadline", I mean an actual, external deadline by which the item must be completed. This is not the same thing as a soft date set by us, when we would like the item to be completed. The distinction here is crucial.

Early in my career, if I had a task and wanted to get it done by the end of the week, I would stick a "Friday 4:00pm" deadline on it --- not because it actually needed to be done by then, but just to put a stake in the ground. The problem with that, is that I had a lot of things I wanted to get done that week and they all had Friday "deadlines". Two things happened. First, the items that really did need to be done by Friday got lost in the crowd, and I'd miss those deadlines. Second, I'd end up with multiple alerts on Friday with dozens of things I needed to do on that day, and no way to complete them all. It was awful, because missing deadlines is demotivating and demoralizing, and I was missing "deadlines" right and left.

If something isn't actually due on a date, don't give it a deadline. Reserve deadlines only for tasks that have real, external dates and times attached. "Submit the grant proposal" probably has a real deadline because it's set externally by the funding agency; "Reply to the department chair" probably does not, although you'd like to reply sooner than later.

If you've determined that the item under review has a real deadline, put it on a calendar and set a reminder. Date-sensitive tasks belong where dates belong: On a calendar, not a to-do list. On the day something with a real deadline is due, you can put it on a daily to-do list if you want; but don't make the mistake of setting deadlines on everything or you will generate so much noise in your system you won't be able to focus on anything.

What happens next

An item that makes it through the filtration from these questions:

- Is actionable

- Can be done in a single action

- Takes longer than two minutes

- Is best done by you (not someone else)

- Doesn't have a specific deadline (i.e. it should be done sooner rather than later but there's no specific date/time constraint)

Put the item on the Next Actions list you made earlier.

The Next Actions list is the closest approximation to a "to do" list that we will have. You may notice that the Next Actions list is a fraction of the size of your inboxes you started with. And this ought to give you a lot of hope. What you're doing here is focusing, by shunting off to separate locations (or to the trash) anything that isn't actually actionable, or takes more than one step, or can be resolved quickly without going on a list at all, or should be delegated away, or which actually belong on a calendar instead. This is way beyond the "to do list" that most academic types make, then struggle with and ultimately abandon --- because those lists are unfocused and bloated. This one is lean, focused, and especially doable.

Conclusions

What you do now, is take the next item from your inbox and go through these questions again, then again for the next item, then again for the item after that, and so on, until the inbox is empty. Then move on to the next inbox, etc. until all of them are empty.

If you're new to this, you probably have a lot of questions. Foremost among those might be: Are you out of your mind? This will take me all day! I'll leave questions about my sanity to my therapist, but it's definitely true that if you've never done this --- you have multiple inboxes each with hundreds or even thousands of unprocessed items in them --- it'll take time. That's why this is a Summer Challenge. During the summer we often do have the time for this. Take an entire day, or even an entire week. Just keep a few things in mind:

- This might go faster than you think because usually there is a lot of un-actionable stuff we capture, or stuff that is just information and needs to be filed away. Once you find the courage to hit the Delete button, things speed up.

- It's much easier to maintain the habit of Clarifying once you do it the first time. Cleaning a house inhabited by hoarders is hard; keeping the house clean afterwards is still work but not as hard. And as Clarifying becomes habitual, you think about the process less.

- Clarifying costs time, but it also makes time because you are making decisions about items in your attention on the front end, and avoiding the Zeigarnik effect.

I'd also say that this process is not really more work, it's just a different way of thinking about work. Remember you're working on these items one way or the other --- either unconsciously and out of your control if you let them sit unclarified, or consciously and in your conrtrol if you clarify them. One form of work is tiring and demoralizing; the other form gives energy and control.

Unfortunately many academics get off the bandwagon at this point, and I suspect some of you reading this far will do that too. But if you are up for the challenge, committing to this habit is a powerful way to make change.

There's actually more to do with this process. We haven't discussed projects yet, what to actually do with the items on the Next Actions list, and several of the nuances involved here. Those will unfold in later posts.

The Challenge this week:

- Continue to do Capture, every day.

- Pick a day in the next seven days and clear your calendar. Then go through each inbox you have and process every item in each one, using the Clariying process to get your inboxes to zero.

- Ask questions in the comments!