Sabbatical lessons, part 3: The hard work of innovation

This is the fourth post --- it's part 3 because I started with 0 --- in an ongoing series in May on my sabbatical experiences. I invite you to check out the first post, the second one, and the third one.

I'm down to the last two weeks of my year-long sabbatical with Steelcase Education and continuing this series on what I've learned during my nine months with the company. To recap: Higher education and industry are more alike than people realize, and higher education would do well to study and adapt the practices of companies that are doing the right things for the right reasons and in the right ways. And the most important facet of good companies that higher ed would do well to study is agility --- the ability to move, as an organization, quickly and easily, and the forward and peripheral vision it takes to do this.

There's another aspect of great companies that also can and should be co-opted by higher education that I wanted to write about this time: Innovation.

Some of you sighed heavily or cringed when you read that. I don't really blame you. But hear me out.

Let's first be honest: "Innovation" is the "Stairway to Heaven" of the academic lexicon. It's a term that is so misused and shopworn, having been trotted out by countless overly-eager academics over the years, that whatever real meaning or inspirational power it used to have is buried under a mountain of bad ideas hatched and implemented in its name. It's a buzzword, used in countless Dilbert-esque mission statements and strategic plans that lose their way the moment they come into contact with reality. It is just the sort of word a person who's been brainwashed by a year-long sabbatical in industry would use when talking about how higher education needs to change.

And yet: There's something still present in the concept of innovation that speaks to the heart of higher education. Just like "Stairway to Heaven", despite the overuse and misuse, its aesthetic and inspirational power is still there, if we're willing to dig for it. (Speaking of heart, if you need a fresh take on "Stairway to Heaven", check out this version.)

One of the books I read on sabbatical was How Google Works by Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg[1], who are Executive Chairman and Senior Vice President of Products (respectively) at Google. Their discourse on innovation, and especially this description of innovation, stuck with me:

To us, innovation entails both the production and implementation of novel and useful ideas. Since "novel" is often just a synonym for "new", we should also clarify that for something to be innovative it needs to offer new functionality, but it also has to be surprising. If your customers are asking for it, you aren't being innovative when you give them what they want; you are just being responsive. That's a good thing, but that's not innovative. Finally, "useful" is a rather underwhelming adjective to describe that innovation hottie, so let's add an adverb and make it radically useful. Voila: For something to be innovative, it needs to be new, surprising, and radically useful. (p. 112, my emphasis)

Most of my encounters with innovation in higher education have emphasized the new but at most one, and often neither, of the surprising or radically useful. When I came out of graduate school in 1997, it was still the heady days of the calculus reform movement and I got involved in Project NExT, which did and still does strongly encourage innovation in teaching. At the time, though, there weren't many who were trying to distinguish between being truly innovative and simply doing new or unusual things in the classroom. My first couple of years in the profession involved a lot of stumbling as I built as much "innovation" --- that is, new stuff --- into my classes as possible. Because if innovation is good, then more innovation is better, right? Well, it turns out that simply doing everything in your class differently than it's ever been done before, isn't necessarily helpful for students. New is not the same thing as radically useful in Schmidt and Rosenberg's terms.

Also, I'd say that when Schmidt and Rosenberg use the term "surprising" as a part of innovation, they mean pleasantly surprising. A lot of my early "innovative" teaching did include a lot of surprises for students --- but not in a good way.

Going into the sabbatical, I had a sense that innovation --- real innovation, not just admin-speak for "new stuff" --- needs to be playing a bigger role in higher education than it does, but I was unsure of how that might look at scale in an organization. So I made it part of my mission at Steelcase to really learn about innovation as it is actually practiced in a company widely known for innovation. So I observed, took notes, asked questions --- and here's what I learned.

First, innovation is hard work. Behind every innovative idea or product that Steelcase produces are hundreds of person-hours of brainstorming, designing, meetings, Agile sprints, and back-to-the-drawing-board moments involving sometimes dozens of people across the company and outside the company. I was involved in a lot of this kind of work. It is expensive, time-consuming, and frankly exhausting for all involved. But it's the only way the company survives, because the moment Steelcase decides that it's just going to make Node chairs and Verb tables forever and nothing else, then any of a number of smaller, hungrier competitors will come along and put the company out of business, even if Steelcase does an excellent job of just making chairs and tables. This is the innovator's dilemma in a nutshell, and it's real.

In higher education, we need to have open eyes about the human and financial expense of innovation as well as the necessity of it. We need to innovate, because the alternatives to traditional higher education are getting more and more legitimate every year, and we run the risk of obsolescence or worse if we just sit on what we know. But asking someone, or some group, to be innovative means asking them to make a big commitment to doing it right, and when we do ask, we need to back up that request with time, money, and other resources to ensure that we're not just ticking boxes off a strategic plan but producing something truly innovative.

An example of a real innovation in higher education is something I'm well acquainted with: flipped learning. (Here's the definition if you're not familiar.) Is flipped learning new? Check[2]. Is it (pleasantly) surprising? I'd say definitely yes, based on my students' responses over the last ten years and reports from the research literature and personal conversations --- the vast majority of students, when asked, comment that flipped learning was a new thing for them and it took some getting used to, but in the end they can clearly articulate the benefits. Is it radically useful? Also yes and for the same reasons.

But is flipped learning easy or cheap to implement? Can a department chair or dean just mandate that faculty start using flipped learning without providing time, money, training, and/or protected status on course evaluations? I think you can guess the answer to that. I wouldn't have proposed a one-year phase-in plan for new flipped educators if I felt based on my experience that this was something you could do immediately and for minimal expense. Most attempts to do flipped learning on the cheap and in a short amount of time end up crashing and burning. It's hard work. All real innovation is.

Second, innovation has to scale. This is a phrase I heard in a conversation with one of the higher-ups at Steelcase during a workshop and I wasn't exactly sure what he meant at first. But later, I realized he was right: In order for innovation to succeed and make a difference in an organization, it has to be done in such a way that it can be picked up and expanded by more people than just the one person or small group that originated it in the first place. Otherwise, that innovation just remains a niche idea.

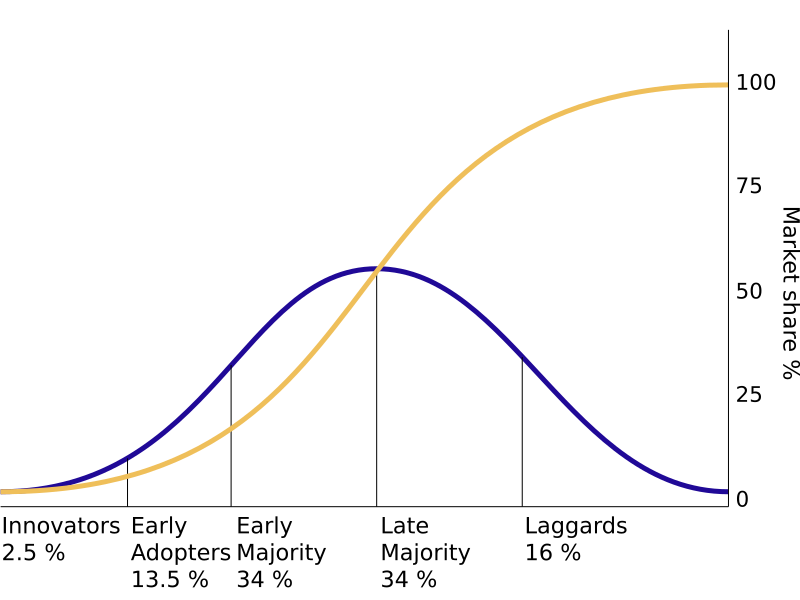

While I was at Steelcase, there was a lot of conversation about how well the company was reaching customers at various places along the diffusion of innovations curve:

Steelcase has done an outstanding job penetrating the market of "innovators" and "early adopters" in education. But that market space is nearly saturated at this point --- most schools in those groups that will ever purchase active learning classrooms, have done so already --- and so the question becomes how to reach the "early majority" market. These are schools that are more cautious about active learning classrooms (or sometimes just active learning, period) and in need of more justification to accept the risks that all real innovation always entails.

Steelcase did extensive market research on this group and found that one of that group's foremost needs --- the item that would make the biggest difference in accepting those risks -- was professional development. Many indicated that if there were human beings at Steelcase that could come alongside them after the active learning classroom equipment was purchased and installed, to help them figure out how to use it best, they would be far more likely to make the purchase. As unsurprising as this may seem, nobody in Steelcase's industry sector is doing this. Providing professional development in active learning pedagogy to go along with the furniture would be a real innovation: new, pleasantly surprising, and radically useful.

But it would be very hard to scale it. Right now, Steelcase has only one full-time employee whose job is (partially) to visit customers and provide professional development workshops on how to use the spaces they've purchased. If this innovation were to be rolled out, the company would need enough staff to cover potentially multiple hundreds of requests for workshops year-round and in all corners of the Earth, and those staff would need to be trained in active learning pedagogy, technology, and space and have the skills to train others. An alternative might be to set up an online professional development resource, like a MOOC, where schools and teachers could train themselves, or to be used as a resource for local experts (like the teaching and learning center). But this isn't what the early-majority people are asking for, and it seems far less useful and therefore less innovative.

Although this would represent a true innovation in this market space, it's going nowhere fast unless the organization can figure out how to make it available at scale. Higher education should take note. The innovations that we sometimes ask for (or, let's face it, mandate) cannot be the sole property of a handful of faculty. The only way innovations survive is to grow, and if that growth isn't part of the plan from the beginning, you might as well invest the resources elsewhere.

Third, innovation has to be everybody's job. In higher education, we tend to assign ownership to big, systemic issues rather than actually tackle those issues. Issue x becomes the sole property of the Vice Provost for x, or the Chief x Officer. Sometimes this is warranted. (For example, if my university's chief financial officer ever cedes any responsibility for the university's finances to me, then God help us all.) At other times, it's a cop-out, and we are taking something important that really needs to be addressed by everyone and turning it into Somebody Else's Problem.

The latter is what I think about when I see the increasing number of Chief Innovation Officers on university campuses. I am not suggesting these positions aren't sometimes helpful or even necessary, or that the people in those positions don't do good work. But I do see in those positions a pathway for universities to shunt the responsibility for innovation away from the centers of power as well as from the grassroots where real work gets done.

Steelcase does not have a Chief Innovation Officer, despite its reputation as one of the most innovative and creative companies in the world. Instead, the reputation comes from the fact that every person at the company feels personally responsible for innovation. I saw this every day I was working with the Steelcase Education and Workspace Futures teams, and on days when I crossed over and worked with other departments as well. Not a single person, ever, gave a hint that innovation and driving the company forward was not partially their job. People were all in, committed to the work, and never, ever slacking off and doing the bare minimum. The sense of energy and intellectual momentum in the building every day was bracing.

Again, higher education can learn from this. It would be a huge mistake for a university administrator, department chair, or faculty member to dream up something "innovative", and then hand it off to someone else to make it happen, and then promptly moving on to something else. The fact is that real innovation, if it's such hard work and has to scale, is everyone's job, and if there is any Chief Innovation Officer in a university, it should be the Provost or President.

Universities have for centuries been the centers of innovation in their societies. Innovation is in our blood. We should return to this idea with fresh eyes and fresh ideas and own it, the way some of the best companies in industry own it.

Images:

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/christineprefontaine/8667743577

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/149561324@N03/

Schmidt, E., & Rosenberg, J. (2014). How Google works. Hachette UK. ↩︎

I argue in my book that flipped learning is not just a rebranding of what the humanists have been doing for centuries --- it's truly a new concept, although maturing since its emergence in the early 00's. ↩︎