How much research has been done on flipped learning? An update for mid-2017

About a year ago, I was hard at work on Chapter 2 of my book where I go into depth on the history, theory, and research on flipped learning. I was especially interested in finding the seminal publications, the required-reading journal articles that a person getting into flipped learning research would need to read, and seeing how flipped learning research has evolved over time. I made heavy use of the ERIC database since it's easy to do targeted searches with date restrictions on ERIC. It was so easy, in fact, that I decided to take a detour one day and look only at the number of publications per year, to address the common misconception that flipped learning is a fad with no research basis.

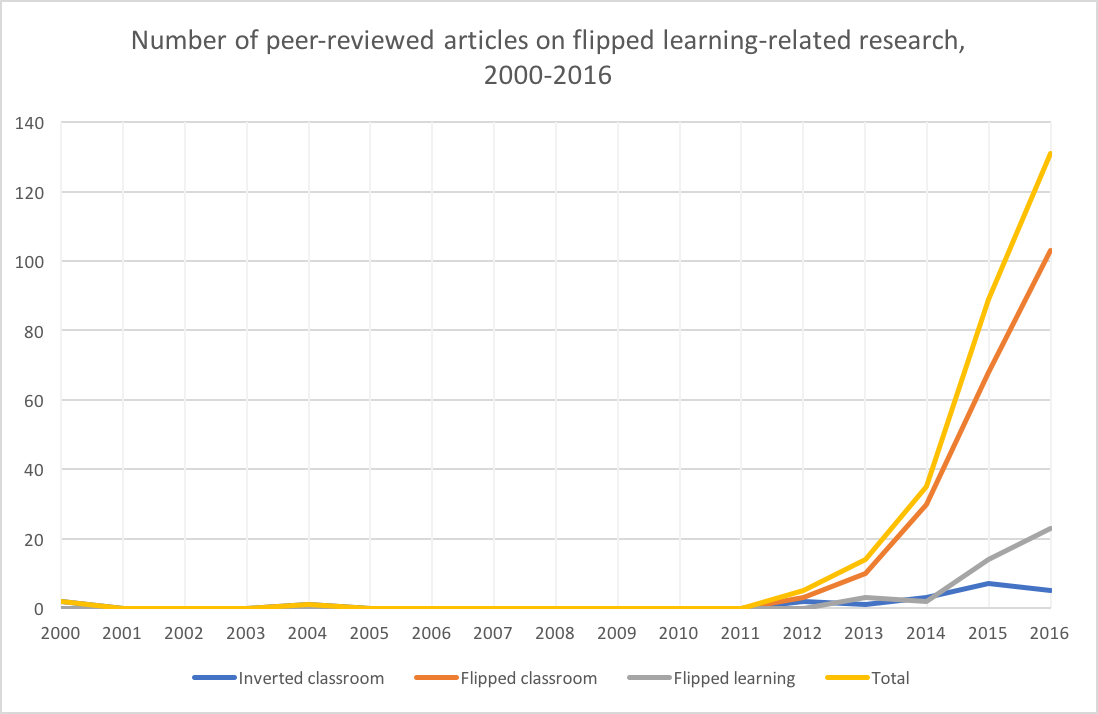

What I found surprised even me, a flipped learning partisan: not only was the volume of research growing, it has growing exponentially since 2012 and shows no signs of slowing down. I wrote about it in this blog post from last summer.

Yesterday, Raul Santiago (who is now the leader of the Flipped Learning Research Fellows group of which I am a part) tweeted that article, and it reminded me that I needed to update the data to include all of 2016 and take a look at how things are going so far in 2017.

First, about the data themselves: What I did here was go to ERIC and run repeated queries using variations on this search term:

(title:"flipped classroom" or abstract:"flipped classroom") and (pubyear:2016)

What this does is find all the articles in the database that have "flipped classroom" in either the title or abstract, and which were publised in 2016. Additionally, there's a "peer reviewed only" button that I checked to filter out only the peer-reviewed articles. When I did the original post last year, I ran this query 16 times using pubyear:2000, pubyear:2001, and so on up through pubyear:2015. Then I ran it 16 more times replacing "flipped classroom" with "flipped learning", and 16 more times using "inverted classroom". Those three terms are the most commonly used ones to describe what I call "flipped learning". The results that come back from this search are what I am considering to be "flipped learning research".

This is nowhere close to airtight, of course. Some of the results from these queries are not actually research articles; for example some are op-ed pieces written for journals. Conversely, some legitimate research items don't come up in these queries, for example Ph.D. dissertations and Master's theses. There are also issues with using terminology, since someone could be doing real pedagogical reseach on flipped learning but not use one of these three terms, or only use them in the body of the paper and not in the title or abstract. And some of the results are definitely double-counted, for example if a paper that says something like "the inverted classroom (also known as the flipped classroom)..." in the abstract.

But, given those limitations, the trends of the results are still pretty striking. I've published both the raw data and a graph of the data here at figshare for you to use, and you can cite the data by clicking the "cite" button. In 2016, there were:

- 5 articles published on the inverted classroom

- 103 articles published on the flipped classroom

- 23 articles published on flipped learning

That's a total of 131 articles. To put that into perspective, the total number of articles on flipped learning was 146, for all of 2000 through 2015 combined. Let that sink in.

Here's the graph:

Yep, still exponential growth. In fact, I ran an exponential regression on the data (transforming the time variable so that year 0 is 2000, year 1 is 2001, etc) and the exponential model was $y = 0.00548171(1.88282)^x$ with an $R^2$ of 0.9799. That's a ridiculously strong fit, and the base of the exponential says that the amount of research is almost doubling each year.

I also took a look at the current numbers for 2017, as of today (almost exactly halfway through the year): 11 "flipped learning" articles, 38 "flipped classroom" articles, and one (rather lonely) "inverted classroom" article for a total of 50 so far. When I did this last year on June 2, the total was 38. The total number for 2016 ended up at 131, or about 3.4 times the number at mid-year. (Most research like this seems to be finalized during the summer.) So it's not unreasonable to predict that 2017 could end up around 180 publications when it's all over.

Or, to put the 2017 numbers in perspective: The entire volume of flipped learning research from 2000 through 2013 was just 22 papers. In 2014 there were 35 papers. We've blown past that already in just the first six months of this year.

So, the quantity of research in flipped learning is truly impressive and it should dispel any notion that flipped learning is a fad that has no basis in research. However, I want to make some observations now about quantity versus quality.

The rapid and sustained growth of flipped learning research is no guarantee that the research results are interesting, useful, or even valid. From my vantage point as a person who reads a lot of these published articles, the whole body of flipped learning research right now feels normally distributed in terms of quality. When I tweeted about this earlier today, I had this short conversation about quality:

There's still some crap and some brilliance and a lot more in the middle, so pretty much like any other research since forever.

— Robert Talbert (@RobertTalbert) June 15, 2017

But it's more complicated than this, because the approaches that are used in these articles varies widely. Some articles are what you might call "lessons learned" articles, where someone uses flipped learning in a class and reports back on what they observed. Other articles, similar to "lessons learned" articles but a step beyond, are "best practices" approaches where someome tries flipped learning, makes observations, and then tries to isolate what works and what doesn't work. Other articles --- and there seem to be more and more of these lately --- are quasi-experimental studies where professors take existing courses with real students in them and have a "control" section and an "experimental" section (non-flipped and flipped, respectively) and introduce some sort of measure, usually learning outcomes or survey responses, and conduct a statistical analysis of the differences in the outcomes. Still other articles are more theoretical, like literature reviews or meta-studies; there are not a lot of these, but 3-4 years ago there were none of these, and the appearance of these studies is, I think, a sign that flipped learning research is starting to mature and enter into a new phase.

These different approaches have different measuring sticks for "quality". There are good and bad "lessons learned" papers as well as good and bad quasi-experimental studies, and the good papers in one bear little resemblence to the good papers in the other. You'll see loads of statistics in the latter, for example, but almost none in the former. However, all the good papers, regardless of style, seem to have some things in common: The authors have done a thorough study of existing literature on flipped learning, know the landscape, and have situated themselves in an appropriate theoretical framework. The authors use good methods that are appropriate for their situation. If it's a quasi-experimental study, the questions are clear and the methods are appropriate. And finally, the most important thing: the paper is simply written clearly, and the authors are honest about what their results say and especially what they do not say.

Likewise, bad papers have things in common too. There are too many failure points to enumerate, but I think the worst is when authors become married to their hypotheses and take every opportunity to interpret their results in a way that supports those hypotheses[1]. There are few things worse than a sales pitch masquerading as a paper.

It's very important to note, too, that peer review is not a guarantee of quality. Some papers that are peer-reviewed and published have very little validity in real life, but they made it through the peer review process because maybe the reviewers didn't know how to review it, or they missed something. Likewise some very good research gets rejected because of bad reviewers, for example people who think that the only trustworthy research consists of either valid mathematical proofs or double-blinded clinical experimental studies in a controlled lab environment. (When you ask those people about the research they consulted for making decisions on how they teach, though, they are strangely silent.)

So is the quality of flipped learning research changing? I think so, but it's a slow movement. Faculty who write these papers are often not trained in educational research (I would include myself in that group) and so a lot of the published work today still has the mark of inexperience. But, we've had enough published work now that the papers that these inexperienced folks are reading are good models and are having a good influence. Those inexperienced faculty will model their work after good studies and so their studies will be better; then in 2018 someone will use their studies to model a new study which will be even better, and so on. I think we'll continue to see this improvement as the quality snowballs. A growing awareness of the importance of the scholarship of teaching and learning, and growing numbers of workshops being given to college faculty on SoTL (for example through campus teaching/learning centers) is also having a big impact on the quality of this research.

There are still some issues that flipped learning research is facing. We are still struggling to find a common operational definition of "flipped learning" for instance[2]. We can't even seem to agree on a common term to use (although "inverted classroom" seems to be dying out). This leads to serious conceptual misunderstandings, for example the belief among authors that video is necessary for flipped learning. There's also a continuing problem wherein authors frame flipped learning as something brand-new, with a lot of "buzz", that nobody has really studied yet. At this point we need to be past this; flipped learning is exciting and the research is still emerging, but as we can see from the data I collected here, it's a long way from being a buzzword or fad or something that has come out of left field. It's a maturing idea and we need to study it as such.

I reviewed a paper once in which students were surveyed about their attitudes about flipped learning after one semester in a flipped course, and something like 40% of responses were strongly negative. The authors' interpretation of this was that 60% of the students liked the course. True, I guess... but that's hardly the result that sticks out. ↩︎

I offer a definition of "flipped learning" in my book that I think really works well. If you buy the book, you'll find out what it is. ↩︎