Words, numbers, or nothing?

This post originally appeared at Grading For Growth on August 2. Grading For Growth is my "other blog", co-written with David Clark. We publish there once a week on all things related to grades, grading, and alternative grading practices. Click here to check it out and subscribe (for free!).

A regular part of the schedule here at Grading for Growth is summaries of research studies that are important or interesting, that pertain to grading and grades. Our first is a classic, referenced seemingly everywhere people talk about grades.

Butler, R., & Nisan, M. (1986). Effects of no feedback, task-related comments, and grades on intrinsic motivation and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(3), 210.

The study is housed here, although there is a paywall.

What is this study about?

The abstract states:

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that intrinsic motivation would be maintained after receipt of nonthreatening, task-related evaluation and undermined after repeated non-receipt of feedback or receipt of controlling normative grades.

Intrinsic motivation is the motivation to perform a task simply because of the task itself, where the reward for doing the task is inseparable from the task. Extrinsic motivation, by contrast, is driven by external rewards. When a person goes for a run because they enjoy the act of getting outside and exercising, that’s intrinsic motivation. When they go for a run because their employer is offering a bonus to employees who log regular exercise, that’s extrinsic motivation.

As teachers, we will work with any form of motivation we can get, but we want to increase intrinsic motivation where and when we can. We care about students. We want them to become effective lifelong learners who not only know things, but enjoy learning things. While extrinsic motivators will always be present, they are not effective for long-term intellectual growth and create dependencies in learners that make it difficult to grow and adapt later in life.

So this study looks at what happens to learners’ intrinsic motivation when they perform a task and then get one of three feedback conditions: (1) informative verbal feedback about their performance, (2) numerical evaluation about their performance, or (3) no feedback at all. Their three hypotheses for this study are:

- Learners who get informative, individualized verbal feedback will express more interest in the tasks than either those who get numerical grades or who get no feedback.

- Performance on qualitative tasks will increase after getting verbal feedback, moreso than after getting either numerical feedback or no feedback.

- Performance on quantitative tasks will increase after getting verbal or numerical feedback, moreso than after getting no feedback.

Notice that not only is the study looking at intrinsic motivation, it’s also looking at the quality of the work as well. Right away, you can see that this study has major implications for how we grade.

What did the study do?

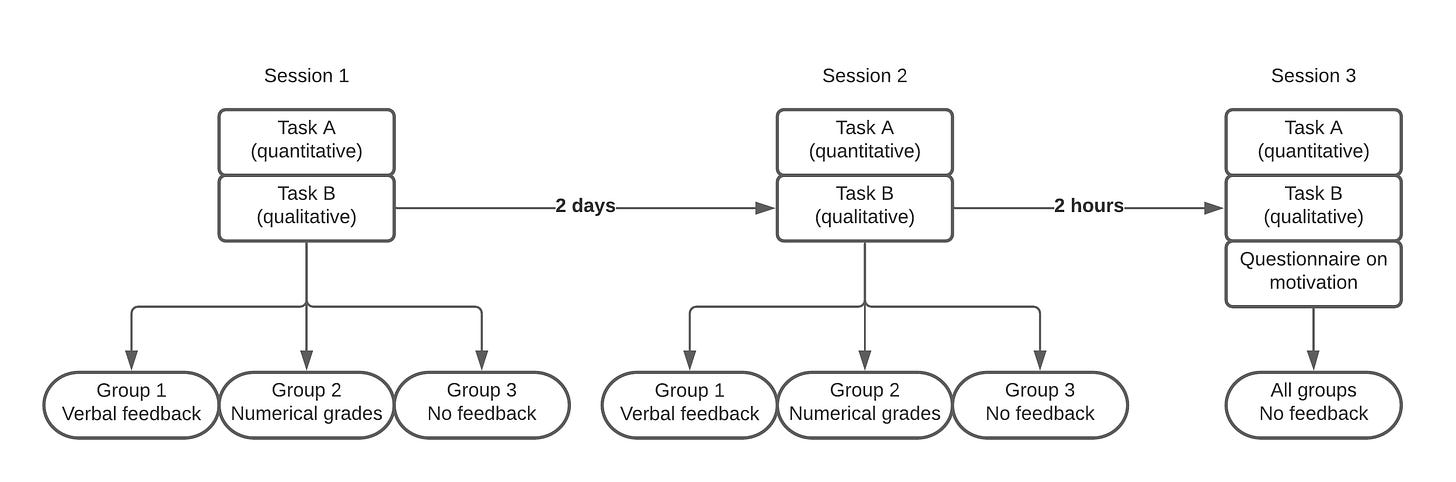

The study’s subjects were 261 sixth-grade children (145 girls, 116 boys) enrolled in three “city elementary schools serving predominantly middle-class populations”. (The “city” here is probably Jerusalem, where Butler and Nisan were located.) The three classes were randomly assigned to three roughly equal-sized groups, labeled simply Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3.

At each of three sessions, each group received a workbook containing two tasks. The first, labeled Task A, was a “quantitative” task that involved constructing words out of the letters of longer words (in the first and third sessions) or a word tree using the first and last letters of other words (second session). Task B was “qualitative”, leading students through some items from a divergent thinking “alternative uses” test. Kids were given 5 minutes to complete each task in each session.

In a two-day period following session 1, the tasks were scored using rubrics based on the number and length of words generated, for Task A; and on more essay-like criteria for Task B. Then at session 2, the kids had their work returned to them. Group 1 received verbal evaluations of their performance. Group 2 received numerical grades. Group 3 received no feedback. (Note that all work was graded numerically using the rubrics in order to do statistical analysis on the results, but only Group 2 got numerical grades.) In session 2, kids worked on the second booklet and their work was handed back with similar feedback 2 hours later. Finally, the kids were instructed to look through Booklet 2 and then told that there were some tasks that had not yet been tried out, and told to try these out (in booklet 3) but that there would be no feedback this time.

The “verbal evaluation” that Group 1 received consisted of a single sentence with two phrases: one related to something the child did well, and one for something the child did less well.

Finally, at the end of session 3, learners got a questionnaire with items related to how they attribute success on the main tasks, the role of effort, and other motivation-related items.

What did the study find?

The detailed statistics of the study are in the paper and we won’t dive into those, but here are the main results.

- For Task A (quantitative), there was a highly statistically significant difference between the verbal and numerical feedback groups (1 and 2) and the no-feedback group (3) (with groups 1 and 2 performing higher) but no significant difference between the verbal and numerical groups.

- In Task B (qualitative), Group 1 (the verbal comments group) significantly outperformed both Group 2 (numerical grades) and Group 3 (no feedback). And, there was no significant difference between Groups 2 and 3 on Task B. And, those significant difference persisted in all subscores of Task B for different elements of student responses.

- Finally, related to the results from the questionnaire about motivation: Group 1 learners (verbal feedback) showed a strongly significant difference (higher) in expressed interest in the tasks compared to either group 2 or group 3 and were much more willing to volunteer for further tasks.

- Also on the questionnaires: Group 1 and Group 3 learners were more likely to attribute success to skill than Group 2. But also, Group 1 was more likely to attribute success to effort than either Group 2 or Group 3. And Group 3 (no feedback) were more likely to attribute success on the task to the instructor’s mood or neatness than either Groups 1 or 2.

- Finally on the questionnaire, the majority of learners in each group stated that they preferred getting written comments, including 78.9% of the kids in Group 2 (numerical grades).

What does it all mean?

This study is quoted in nearly all of the current literature and publications about grades for good reason: It makes a compelling case for emphasizing verbal feedback in student evaluation and de-emphasizing, if not completely eliminating, numerical grades. In this study, verbal feedback not only was linked to significantly improved intrinsic motivation in the subjects but also to improved quality of performance on both computational and written tasks.

In fact, on Task B (qualitative), there was no significant difference in performance between those who got numerical grades and those who got nothing — in other words, statistically, you might as well not even evaluate a student on qualitative tasks (such as proofs, essays, etc.) at all, if all you’re going to do is give them a number.

However, keep your filters on: This was a study done in a particular location, at “middle class” serving urban schools, with sixth-graders. And the tasks here were deliberately (and appropriately) generic. None of those conditions is exactly like the ones that you or I may be teaching in next year, or ever! So as with most educational research, even the best studies have external validity issues.

You might be an instructor in a situation where making a wholesale change in your grading approach, especially so close to the beginning of the new academic year, isn’t really an option. I think this paper, in addition to giving you a lot to think about and discuss with your colleagues and students, provides some ideas for making small changes now that can set the stage for bigger ones later. First, the verbal feedback that the Group 1 kids got in the study was just one sentence long: One phrase about something they did well, another about something they did less well (e.g. “You wrote a lot of words; but not very many long ones.”) Providing useful verbal feedback doesn’t require writing a novel; in fact short, to-the-point feedback is arguably more useful to students. Also, it’s possible that replacing numerical grades with verbal feedback in spots might produce positive effects. For example, if you currently include three essays in your current syllabus as part of an overall grading scheme, and you use points to grade those, try not giving points on just those, this time, and seeing how it goes.