Negative results about flipped learning from a randomized trial: A critique (Part 2)

Back in January, I began a two-part post breaking down this paper published through the School Effectiveness and Inequality Initiative at MIT. This paper gave results from a controlled study of flipped learning in math and economics at West Point, and those results didn't look good for flipped learning. Between then and now, the world went sideways and I never made it to part 2. But last week, part 1 got some unexpected traction on Twitter, and since at least a few people are interested, I'm circling back now to finish my thoughts.

Recap of the study and its issues

In the study, the authors looked at students at the US Military Academy (known by its location, "West Point" ) enrolled in introductory sections of calculus or economics (n = 1328, with 80 sections under 29 instructors studied). The students were randomly assigned to either control sections where the instruction was entirely traditional lecture, or experiment sections which involved flipped learning. The authors looked at student performance measured via a quiz over the units (same quiz for both control and experiment) and on two final exam questions, as well as the overall final exam scores.

The authors looked at the differences between flipped and non-flipped sections in the short term (via the quizzes) and the longer term (the final exams) and across gender and socioeconomic groups. The authors were asking: Does a flipped learning environment have a positive causal effect on student learning? And do such effects persist over time and across socioeconomic classifications?

What they found was:

- Achievement gaps between white and non-white student groups, between men and women, and between high-achieving and lower-achieving students not only did not close as a result of flipped learning, they got worse.

- Even for those who appear to reap the benefits of flipped learning – which appears to be a highly privileged group – those benefits were short-term only, meaning there were short term gains (quizzes) that did not persist into the long term (exams).

Not good, right? However, I pointed out in the previous post, there are a number of issues with this study that cast doubt on the results, including:

- The study underwent no peer review. This is a "discussion article" that, at least as of January 2020, had not been published in a peer-reviewed journal article --- it was just posted to a website. It's basically a preprint. That places limits on how much confidence we can possibly have in the results.

- The definition of flipped learning being used is either unclear, or clear and wrong. The authors never really define the concept of "flipped learning". When we get a glimpse of what the authors mean, we learn that they mean "students learn the material by watching video lectures prior to class". In part 1 I go into great depth about how this is idea is incomplete, impoverished, and ultimately wrong.

As we move through the rest of the paper, we find that the issues don't stop there.

The literature review

Normally in a research study, the research questions are situated in the context of what's already known, by conducting a brief but thorough review of previously-published research that pertains to the questions. This isn't merely a formality. Authors need to do this review to make sure their research is truly novel, to avoid the mistakes of others, and to establish a valid theoretical framework for interpreting their results. Readers need this review so that they can have a basis for thinking critically about the authors' results.

So it's alarming to see that this paper basically does not have a literature review at all. It starts with a general description of flipped learning (which is partial and flawed) ending with the statement: "Despite the proliferation of the flipped classroom, little well-identified evidence exists on its impact on student learning." At the bottom of page 3, there's also the statement: "Descriptive flipped classroom research finds mixed results" with a footnote that contains eight references. This doesn't constitute a serious attempt at situating the research questions into the context of what's already known.

Let's begin with "little well-identified research exists". A statement like this might be made because although the paper was posted in 2019, the study itself happened in Fall 2016, and there wasn't as much published research in 2016 as there was in 2019. However, there are citations in this paper from 2018. If there was a lit review done in 2018, where are all the papers from 2017-2018? In fact, where are all the published papers on flipped learning at any time? Looking at the references and focus in only on the actual research articles --- not op-eds, the Bergmann and Sams book, etc. --- there are only seven research articles mentioned, and those are from 2000, 2013, four from 2014, and one from 2018.

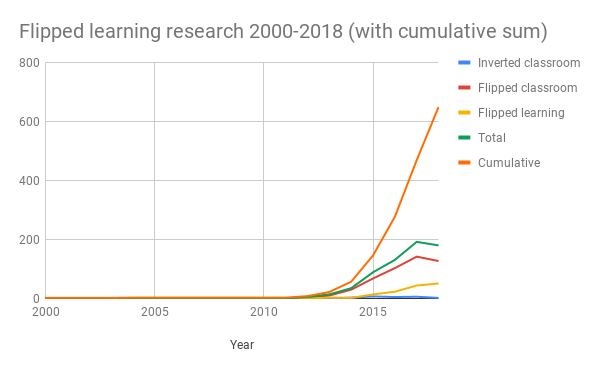

As I discussed in last year's annual "how much research has been done" post: Prior to 2015, there were 57 peer-reviewed research articles published. In 2015 alone, there were 89 research articles published. From 2015 through the end of 2018, there were 592 research articles published. This does not count anything published in 2019, the year the paper was posted!

So far from there being "little well-identified evidence" on the efficacy of flipped learning, there are in fact multiple hundreds of peer-reviewed research studies on flipped learning that were available to the authors at the time the paper was compiled. Not all of those studies are high quality, and not all of them come out in favor of flipped learning, but that doesn't matter --- it's just flat-out wrong to say that "little well-identified evidence exists" when even a cursory search will turn up way more than seven studies.

This lack of depth in the literature review is really baffling, since it's so easy to find these studies and so important to incorporate them. Without a review of previous research, all kinds of doubts arise, including whether the study has any construct validity (my issue with their definition of flipped learning is a symptom of this) and whether the authors have as sound of a grasp as possible on the ideas that they are studying.

Internal validity

Let's shift gears and consider the following analogy:

Imagine I'm designing a medical study to determine if over-the-counter liquid flu medicine is really as effective in treating the flu as the advertisements say. So I gather a group of 1000 subjects and randomly assign them to control and experiment groups. The control groups get no medicine at all. The experimental groups get liquid medicine: exactly one dose of one milliliter of the medicine, given exactly three times (on a Monday, Wednesday, and Friday), spread over one week; and we don't start administering it until after the subjects have had the flu for two weeks. We find no significant changes in the health of the subjects, and in fact some subjects got worse after the medicine was given. Therefore we conclude that the medicine is not as effective as advertised and might make things worse.

You should have a lot of skepticism about the results of this hypothetical study. Among the many questions that should arise are:

- Is one milliliter anywhere near a strong enough dose to have an effect?

- Similarly, is just three doses enough of a treatment to have an effect?

- Why did we wait two weeks to start the treatment? Shouldn't it be started right away and administered continuously?

- I might expect an effect from a drug with such a light treatment schedule if the drug happens to be extremely strong. Is it?

All these are questions about the internal validity of the study, that is, whether the cause-and-effect link between treatment and response is trustworthy.

Education is not medicine, and pedagogical methods are not drugs. But when studying teaching and learning, this analogy isn't strained. A teaching method different from the norm (lecture), if done lightly and only for a short period of time, and not introduced until well after the norm is established, cannot be expected to produce results unless it has extraordinary instructional power. I've found this to be true particularly of flipped learning, over 10+ years of frontline practice in the classroom and working with other teaching faculty. You can flip a class partially, but you cannot flip one tentatively. It takes sustained commitment, otherwise the learning culture of the class will never adapt to build the habits and support needed for student learning to change.

Unfortunately, a tentative approach is exactly what happened here. The experimental sections at West Point received just three class sessions of flipped learning, done in the middle of the semester. So from the students' perspective, they experienced seven weeks of pure lecture pedagogy, then a week of flipped learning, then seven more weeks of lecture. The study found no long-term improvements in student achievement in the flipped learning sections. And why should it? Well over 90% of the course was something other than flipped learning. It's possible the students didn't even remember it by the end of the course, and experienced the treatment as little more than a weird annoyance.

But as mentioned above, a light dosage of a drug might be expected to have an effect if the drug is powerful. How much instructional "power" did the implementation at West Point have?

We know from the paper that that students were "tasked" with watching 20-minute long[1] videos prior to the classes that were flipped. By "tasked", we mean students were sent instructions to watch the videos before class, that their activity would be tracked by the instructor, that it would be important to watch the videos, and that they would lose participation points for not watching. In class, students had time for Q&A over the videos and then worked on problem sets of 10-15 practice problems linked to the lesson objectives and covered in the videos[2].

What we don't know about this is important. What were students doing when they watched the videos? Did they have exercises to go along with them? Were there embedded quizzes? Was there a guide given that showed the links between the videos and the learning objectives? Or, were students simply told to watch the videos, or else? And about those problem sets: What was on them? Were they just basic tasks, or did they build on basics to get students engaged with the middle third of Bloom's Taxonomy? Were the activities aligned with the assessments?

In general, what were the students doing, what was the instructor doing, and why? Without full disclosure here, we have no way to tell the instructional power of the treatment.[3]

To sum it up, the usage of flipped learning in this study didn't last long enough to produce trustworthy results; it didn't take place until a learning culture of pure lecture had already been well established; and there are too many unknowns about what actually went on in the various components of the flipped instruction. I have other issues too, like the fact that the only measures of student performance were one quiz and two final exam questions, but perhaps I've made the point enough.

Issues with external validity

Let's go back to the flu medicine study. We had a good sample size of n = 1000. But suppose those subjects are all top high school athletes in outstanding physical shape, who (on their own initiative and not as part of the study) are highly self-motivated to engage in regular physical exercise, good sleep habits, and healthy diets. Furthermore, those subjects had to pass a rigorous physical exam and get letters of reference from the top doctors in their area in order to be considered for the study.

Again we'd have questions. You have to be thinking --- these people are not most people and I'm not sure that medical studies on these folks really apply to slobs like me. In other words, you'd wonder about the external validity of this study --- whether the results, while valid within the sample, generalize reliably to the whole population.

The West Point study has significant issues with external validity due to the fact that it was done at West Point. Let me be clear: I hold the United States Army and the US Military Academy in the highest regard. I've known faculty at West Point personally and they are dedicated, skilled teachers. And West Point, frankly, sounds like an awesome place to work. But it is objectively true that West Point, while in some ways similar to many mid-sized liberal arts universities in the United States, is almost totally unlike any other university except for the other service academies, and West Point students are categorically different from average college students.

For one thing, West Point students are academically elite. The mean scores on the SAT tests for West Point freshmen are 625 for Reading and 645 for Math. These scores are on par with a place like the University of Michigan, which is considered an elite public institution. At my university, by comparison, the average Reading scores range from 480 to 585 and the Math scores from 480 to 580. West Point students are also highly motivated, having gone through an incredibly rigorous admissions process that includes intense physical testing and letters of recommendation from Senators or Congressmen. It's also worth noting that incoming cadets can't be married, can't be pregnant, and can't have serious physical disabilities.

West Point itself, of course, is a military academy, legendary for its regimentation and discipline. This makes the academic culture and the day-to-day activities of being a student almost completely unlike that at any other university. Since West Point graduates go directly from university into military careers as officers, the link between grades and career is direct. The study mentions, "Students are highly incentivized to do well because grades determine job placement" which is quite an understatement.

None of this is either good or bad. It's the kind of environment that the US Army wants for its emerging officers, and I have no problem with it (and, it's none of my business). My point is that studies done at West Point on West Point students have built-in significant limitations on external validity. What works for my highly diverse collection of students may not work in a military academy and vice versa.

External validity is almost always an issue for pedagogical studies, because those studies are usually done in situ and differences in institutions and populations are hard to avoid. Usually studies will acknowledge this. One thing that bugs me about this study, though, is that not only does it not acknowledge the obvious distinctions of the institution and its students, it treats these as a strength. Repeatedly, the authors write things like this: "The course standardization and randomization of students to course sections makes West Point an ideal place to study the flipped classroom." But this is like saying, in our flu medicine study, that the similarities shared by our top-condition, highly-motivated high school athletes make them ideal subjects for studying flu medicines. There may be some truth in this, but it distracts from the issues inherent in working with such a standardized sample.

Conclusion

It feels like I have thoroughly trashed this study, but I want to reiterate what I said in part 1: We need studies like this, with at least an attempt at methdological rigor, and we need to listen to negative results, even and especially if they are about Our Favorite Teaching Method. I am indebted to Setren et al. for providing us with a study that, for all its flaws, represents an approach I hope that others emulate.

The way to emulate this would be to adopt the authors' use of randomized control trials but fix the flaws I've brought up, namely:

- Situate the study in the context of existing research on flipped learning to have a sound theoretical framework for what questions to ask, what interventions to take, and how to measure the results;

- In particular, be clear about what is meant by flipped learning by adopting a well-vetted definition of the concept;

- Give flipped learning more time and space in the experimental sections --- either a complete, semester-long conversion to flipped learning or a partial flip where one class session per unit is flipped, so that flipped learning is part of the DNA of the class and not just done in a "drive-by" fashion;

- Be more intentional about how flipped learning is actually done, particularly how pre-class work is done;

- Use a more diverse population, or like the Hake 6000-student study conduct the study in multiple institutions and aggregate the results; and

- Use a multiplicity of metrics, not just a quiz and two exam questions, and including qualitative data from students to triangulate the quantitative results.

The length of these videos is a problem unto itself. ↩︎

Interestingly, despite the study repeatedly touting "standardization across sections" as one of its main strengths, different instructors ran their course meetings quite diffently, with some letting students work through the worksheet uninterrupted while others worked through one problem at a time. These variations between flipped learning sections were never discussed in the study. ↩︎

This isn't the first time that a pedagogical study out of West Point has somehow completely omitted any discussion of the actual pedagogy used in the course. This famous/infamous study about laptop usage in West Point classes claims that laptop use hurts student performance and is often used as a pretext for banning laptops in classes. But the study itself makes absolutely no mention of what actually went on in the classes that were studied. A pedagogical study that makes no reference to the actual pedagogy used, cannot be believed. ↩︎