Maintaining humanity in higher education in a high-tech world

Background: Yesterday I had the honor of speaking to a strategic planning retreat for Holyoke Community College in Massachusetts. My 12-minute talk, titled "Education Today and Tomorrow: Maintaining the Personal Touch in a High-Tech Learning Environment", revisited some ideas I spoke about at a similar event at Macomb Community College in August 2019, just before the pandemic, with some reflections on what's changed and what's stayed the same since then. I think these lessons are important, especially for two-year institutions but really for all of us in higher education.

I don't usually speak from a script, but for time-constrained remote talks I make an exception. This post is an edited version of that script. The slides are here, if you're interested.

The last time I gave a talk to a two-year college going through a strategic planning process was in August 2019. The world had not yet heard of Covid-19, and we were somewhat naively thinking about mission and vision for five years into the future. I can't even remember what the main issues were that this college was trying to address. But I was speaking on the same topic I'm going to address with you today -- maintaining a personal human touch as our world and particularly higher education becomes increasingly technological. Little did we know how real this issue was about to become.

We will be processing the lessons of the pandemic for many years to come, but one thing has become clear: The issue of how to maintain the personal touch in a high tech learning environment is not going away just because we are meeting in person again. The issue is really, how do we become human and stay human in the way we teach and learn? This goes way beyond the pandemic, way beyond our strategic plans. It's at the heart of higher education itself and a question we must deal with if we are to remain relevant.

Students vs. learners

An entryway into the main idea for today comes from some terminology that shows up a lot in strategic plans and mission statements, and that's the language of student versus learner. We're going through a strategic plan update at Grand Valley now too, and the current draft of the plan quite studiously uses the word "learner" and not "student". This has prompted some pushback from faculty who think that's buzzwordy and we should stick with the more common term "student". HCC's current plan refers to "adult learners" but otherwise the word used is "students". Is there really a difference?

I really think there is, and an important one. A "student" is a person who is officially enrolled in a formal educational process. A "learner" on the other hand is a person who learns, or is learning. You can absolutely be a student, without being a learner. Maybe you've noticed this. Sometimes a person can be on the books for a class but their interest in learning is essentially zero. On the other hand, you can just as surely be a learner without being a student. I'm an example -- I learn, and I like to learn, although my interest in going back to school is essentially zero. Being a student is a matter of paperwork. But being a learner is a matter of the heart.

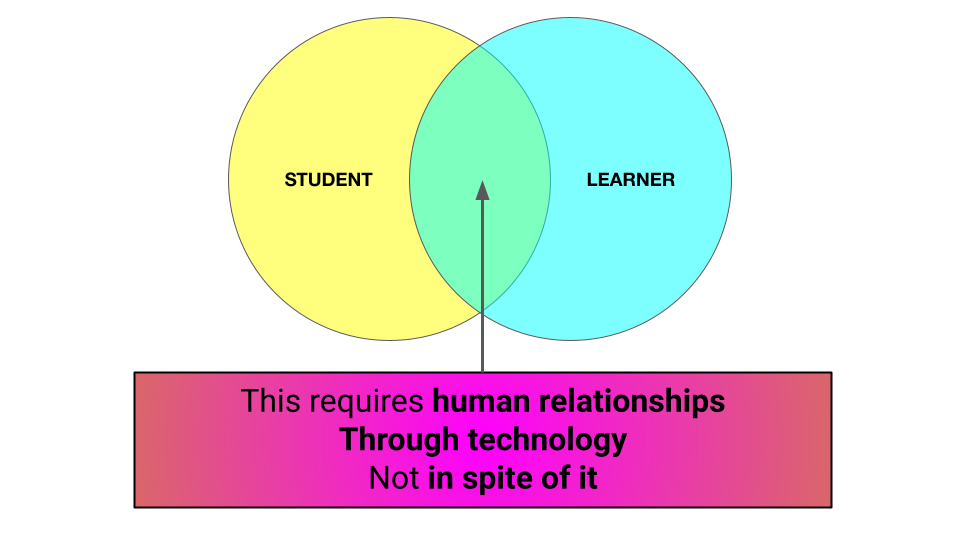

What we hope for --- what our institutions are predicated on, and what your strategic plan at HCC and mine at GVSU must drive toward --- is getting as many people as possible into this intersection area here. Making all our students learners, and going out and finding learners and making them our students. This cannot happen outside the context of human relationships, and second, those relationships can be built and grown through technology, not in spite of it.

It's a mistake to think that we are fighting a war against technology to have human relationships with our students and with learners everywhere. It's a fight, no doubt, but technology is not our enemy. Technology, in fact, can be our critical strategic advantage in this work if we have the will and the creativity to see it that way.

Communication

Ten years ago, it was still unusual to see faculty and students interacting in any way other than in person or through one-directional emails, or maybe an email blast out to the whole class. In-person communication is wonderful – but can be problematic for those who have troubles being physically present. That's a problem that was just an annoyance in 2011 but is an ongoing reality now. Today, though, we have technology that allows me to connect with you and vice versa that is simple and therefore highly useful. Just look at this talk and the chat that's taking place as an example.

Technology also allows us to communicate in ways other than plain text. Plain text is great, right up until the point that you need to share a picture or a video. Tools for communicating using multimedia are better than ever. Many students understand concepts better when translated out of text and so it's high time our tools no longer give preferential treatment to text.

And finally as a corollary, technology allows us, and our students, to do more than just shoot emails and announcements at each other. We can finally use communication tools to actually communicate: to have a rich, honest, multi-way discussion about learning and learning environments. During the pandemic a lot of us discovered that one of the best things we can do in our teaching has nothing to do with pedagogy as such – it was simply taking the time to check in on students, to ask them how they are doing, to ask them what they need, and then act on their responses and check back in to see if things are better. Technology today clears the way for a virtuous cycle of feedback that can be used for learning, for sure, but also just to be human with each other.

Connection

Psychology research tells us that to become intrinsically motivated in a task, we must in part experience connectedness. The task cannot just be something that is done in isolation. In higher education, there are three directions of connectedness.

One is humans connecting to other humans. That's what communication is. Just remember, technology is our ally in this. The tools for communication -- real communication, where we are real with each other and deeply in touch with each other's human needs --- are better now than they have ever been. Yes, it's annoying when students text or chat during class. But this just goes to prove the point: Learners want to be connected. So it's on us, as higher education professionals, to provide avenues for connecting with each other than are more compelling in the moment than a group chat.

We also want ideas to connect with other ideas. Becoming an expert learner involves the habit of not just storing new information and skills, but connecting every new thing you learn to a network of things you already know. When I teach discrete mathematics, I don't want my students to just learn how to compute a binomial coefficient and then later on just learn how to count permutations. There is a connection between those two ideas and I want students to deeply understand that relationship so they are not learning two things, but one thing. We have a trove of tools for forging those connections today --- mind mapping software, wiki-style tools like Notion for note taking that connect notes to other notes, simple tools for drawing or diagramming to make visualizations.

And perhaps most importantly, we make connections between humans and ideas. A huge lesson from the pandemic is that learners want to know why they are learning what we are teaching. The best and possibly the only way to get there is for every learner to forge a personal relationship with the concepts they are studying. My students' understanding of discrete mathematics needs to be the result of a personal journey coming to terms, their own terms, with the concepts and why they are significant. If I asked you to make a mind map of this talk so far, you are forced to make it personal, and you will remember it better, and be able to apply the ideas better mostly because this talk is no longer something I am doing to you – it's a personal experience.

Creation

Creativity is the highest expression of learning, and it's a proper end goal of every course we teach. I know my students have learned, say, differential calculus when they can take data, create a model for it with a function, and then use the tools of calculus to communicate about how the data change over time and also discuss the limitations of the model.

I can see three ways that technology can be used fruitfully to enable creativity.

One is to change the way we assess students, moving away from testing students for simple possession of knowledge and instead giving them opportunities to create things. There may still be a place for assessing students on fundamental domain knowledge, in a simple form. But I also need to teach math as if computers existed. I can't ignore the existence of free computational tools like Wolfram|Alpha any more. Instead, what's needed is a shift in the kinds of assessment I use --- assessment based more on creating, whether that's creating a computer model or creating an algorithm or computer program or just creating a tight, correct technical explanation of a concept. Tech-enabled authentic assessment is a lot more real to students, and the distance from there to their futures is much shorter.

This gets at a second way tech can help here, which is to get the learner involved in their own learning process. The literal meaning of the word "involve" is something along the lines of what happens when you stir creamer into coffee. It means "to turn into". So the creamer, when "involved" into your coffee, becomes a fundamentally inseparable part of what you drink. When learners are "involved" in their learning, they become inseparable from the learning itself. It's the same idea as connecting the learner with the ideas they are learning. The kinds of assessments that center on creativity will, by definition, involve the learner in this way.

Third and finally, using technology to get learners involved in their learning and build their creativity is not just pie-in-the-sky hippie talk. It's a critical element of career preparation in a world increasingly taken over by automation. Employers today don't care what a person's GPA is, and they honestly don't care that much about how much domain knowledge a person has. What they do care about, is can their new hires learn quickly? Can they teach themselves new things without a lot of supervision? And can they provide creative solutions to the problems we face, or will be facing?

It's hard to imagine serving learners well if we don't teach with this in mind, or build our strategic plans with this in mind, and use every tool – digital or analog – at our disposal to make this a reality. If all our students can do when they graduate is follow directions and do what the teacher tells them, then they are dead on arrival in today's workforce, and we have failed them.

Three takeaways

First: Let's remember that the "human touch" is not something added on to an education. Human connection and relationships are how learning happens in every case. Every significant thing you ever learned happened, or is happening, in the context of a human relationship.

Second: In the ongoing process of building relationships with learners, technology is not our enemy despite how it may look sometimes. In fact when used judiciously, technology can be our biggest ally. The real enemy? Indifference.

Third: Although these aren't disjoint, three big buckets for how to use technology to humanize education are communicating, connect, and create.

The work of higher education has always been and will continue to be challenging. The pandemic didn't really change that. But it did bring into sharp focus the necessity of creating a human experience for our learners. It's not easy. But if we keep learners in mind and strive first to give them that human experience, we won't go too far wrong.