Is traditional higher education in trouble from online course providers?

Coursera, the online course provider, is doing well these days. Following their IPO in March, they earned 102 millon dollars in revenue and almost 62 million dollars in profits, and added 5 million new customers --- in just the second quarter of 2021. Their revenues are up 69% from this time last year, and their "enterprise" customers --- companies, not individuals who are paying for their courses and certificates --- are up 109%. All of those figures beat Wall Street predictions.

You'd be hard-pressed to find a traditional university whose financial numbers are anywhere close to this. Many are struggling to tread water right now, and the pandemic plus the demographic apocalypse that was already predicted paints a picture of a rough road ahead. Financials are not, and should not, be the primary measure of success or quality in higher ed. But they're not nothing, and if Coursera's eye-opening numbers are in any way an accurate indicator of people's preferences for post-secondary education in general, then you have to start wondering: Have the online course providers, and their MOOCs, finally caught up with traditional higher education? Is traditional higher ed in trouble?

I'm going to answer this with a definitive Yes, but actually no. Given my recent experience completing the six-course Project Management certificate offered jointly between Google and Coursera --- which by all measures should be the state of the art in massive online courses --- there are real reasons traditional higher education ought to be paying careful attention, but also some advantages that we in traditional universities still have that keep us ahead of the competition... for now.

My POV

I've been in traditional higher education for 33 years, 9 years as a student and then 24 as a faculty member. I've also taken dozens of online courses from providers like Coursera, edX, and Udacity --- even finishing a lot of them. I started taking MOOCs around 2012 when they first arrived on the scene and everyone was terrified we would be losing our jobs to them. I wanted to see what the hype was all about first-hand. So, I took an Introduction to Computer Science course from Udacity and was really impressed. Maybe there's reason to be worried, I thought.

But after I took a few more, I stopped worrying. With most of them, the course design was amateurish, the pedagogy boring and ineffective. One MOOC, from a well-known elite university, was nothing more than a series of 30-minute lectures recorded by a guy sitting behind a desk the entire time. Passing the course involved watching these lectures and then taking a series of multiple choice quizzes. Each quiz item had four options; and you could retake each quiz up to five times. Which means that you could earn 100% on each quiz just by repeated guessing. After giving it an honest go at first, the course was so mind-numbing that I just put the lectures on play and muted them while I did housework; then did guess-and-adjust on the quizzes without even reading the content. I passed the course with a 100%. So... no worries.

That was around 2014. Since then, I've taken more of these courses, and I've noticed they've gotten steadily better over time. When Google announced their certificate programs, I paid attention, and so did others. I decided to sign up for the six-course certification in Project Management because first of all, I like project management; I'd taken other online courses in project management and wanted to learn more. And second of all, I wanted to see what a Google-produced online course looked and felt like. With the combined resources of Google and Coursera focused on a course, surely that would represent the best online courses have to offer.

I finished the certification last week, four months and six courses later. So, are we traditional higher education folks in trouble?

Yes.

Based on what I saw, there are good reasons that traditional higher education should be nervous about the state of the art in online courses and certifications.

- The content, and the platform housing it, is way ahead of most college courses. The courses in my certification featured professional-quality videos with embedded quizzes, well-designed templates for assignments, and an LMS that never crashed or malfunctioned. Coursera is optimized for this kind of experience and spends a lot of resources making sure everything works. Add Google's resources to that, and you get a truly professional-grade content platform. Most universities and individual faculty, despite whatever intentions they may have, just can't keep up with that.

- The course design was excellent. There was a lot of care, smarts, and attention to detail put into building these courses. The lessons were focused on concrete learning objectives; the activities aligned with the objectives; and the assignments aligned with the activities. The course tools (mostly Google Workplace documents, of course) were simple and familiar, and we were given more advanced tools like Asana to explore. The outside materials for reading were informative and gave me a small library of reference materials. There was very little fluff or extraneous elements, and nothing out of place. It was clearly the result of a team of instructional designers bringing the best of what we know about good course design to the job. Again, an overworked, under-resourced faculty member or department left to their own devices is unlikely to produce something that good, even if they knew how and wanted to.

- The pedagogy was surprisingly pretty good. There was still a lot of lecturing, but at least it was focused and brief --- always on a single idea, never more than 6-7 minutes long, and often broken up by ungraded quizzes. I was surprised at how much active learning there was, too, with activities that required me to actually apply what I was doing. Things have come a long way from 30-minute talking head lectures followed by cheatable quizzes. And, again, it's pretty far ahead of a lot of homegrown traditional college classes, online or F2F, which --- still, even now --- cling to the lecture as if their existence depended on it.

- There was no trace of top-down authoritarian power structures. None of the courses in the certification had "instructors", strictly speaking. Instead, they used Google employees (different ones for each course) to serve as guides, who delivered the lectures and put a human face on the material. But there was nobody "in charge" who could have been seen as the gatekeeper for all this knowledge. The Googlers speaking to the camera were just ordinary folks (and a diverse group of them) who also just happen to be project managers. They were not Ph.D.-holding authority figures lording their education over students. This is a major shift from traditional higher education, where the learning environment is, with rare exceptions, centered around professors rather than learners. This absence of a clearly-identifiable professor is not an entirely good thing (see below), but it was frankly refreshing, and I expect many learners felt much more at home in the course because of it.

- Coursera never gets tired or burned out. I hate to bring this up, since many of my colleagues are struggling with the physical and emotional issues brought on by the pandemic. But it's a plain fact that Coursera is not struggling with those issues. Or, if they are, then it doesn't show in the end product. No matter where things go in the world from here, while individual college faculty will continue to get tired, burned out, and ready to quit, Coursera simply won't. It will continue to put out courses that have all the positives I just mentioned, and will continue to improve. Because that's what they do. If traditional universities make our competition with the Courseras of the world all about our enthusiasm and passion versus the cold corporate product of a MOOC -- we'll lose.

There also seems to be little doubt that demand for programs like these is growing. Alternative approaches are being accelerated by both the pandemic and the growth of automation. Most universities seem to disparage rather than explore these kinds of offerings, although there are some surprising names beginning to move in this direction. Private companies are beginning to get impatient waiting for traditional universities to get on board and are beginning to partner with third parties like Coursera, or even just doing it themselves.

So yes, there's good reason to think that traditional higher education could be in real trouble.

But actually no.

Despite all of this, I still think traditional universities hold a decisive advantage over online courses at scale like those offered through Coursera. Let me explain with some anecdotes.

To complete a course in the Project Management certification, you complete all the activities at a certain threshhold of quality. For example, some of the lectures were followed up by quizzes that required 75% or more to "pass". And the centerpieces of the course were extended, high-level exercises where we worked with a fictitious project --- a restaurant that was rolling out tablet-based menu ordering on physical devices --- from inception to closeout. Those involved constructing documents (a project charter, emails to stakeholders, etc.) that were peer-graded.

The low-level quizzes were easy, which is fine because they're low-level. But the high-level assignments --- where the real learning in the course should be happening --- were a bit of a mess:

- Many of the documents we created for peer review were graded on rubrics that only looked at whether certain things were present or not, rather than the quality of the product. For example a rubric might say Give the project charter 3 points if there are at least three goals listed. Whether the goals that are listed are good, appropriate, or well-written was generally not taken into account.

- Even if the quality of the document were actually part of the rubric, the peer grading wasn't regulated, so there's nothing to prevent a peer grader from just giving full credit for a terrible product --- or no credit for a great product.

- And if you actually did get downgraded for poor quality, there was no real mechanism for getting feedback and improving the work. Most of my assignments got no feedback other than "Great job!" even if they weren't a great job.

The one peer-graded assignment I turned in that did not get enough credit to "pass", was incorrectly graded. The document was an email and we were to receive one point per part of the email that was turned in (1 point if you have a subject line; 1 point if you start with a greeting; etc.). Mine had all those but a peer grader gave me 0/5 anyway. So, I just turned around and resubmitted the exact same work and got 5/5. I have to believe other learners might have been downgraded for work that was genuinely poor, but if they were lucky enough to get a peer grader who cared enough to actually assess the work and give feedback, the learner could just ignore the feedback, turn in the exact same work, and get a less conscientious grader the second time who gives full credit sight unseen.

To be clear, I enjoyed the entire certification and feel like I learned a lot. But I also feel like I could have learned a lot more, except there was something missing. So, what's missing? Only the most important element in all of human learning: the feedback loop.

Human beings learn through feedback loops. We try something; we get feedback on it from someone we trust (it often helps if they are experts); then we reflect on the feedback and include it into a next iteration. And we continue that loop until what we are trying to do is "good enough" by some trustworthy standard. These feedback loops require the presence of a trustworthy content expert who can, and does, interact with learners' attempts on an individual level, in a sustained way over time.

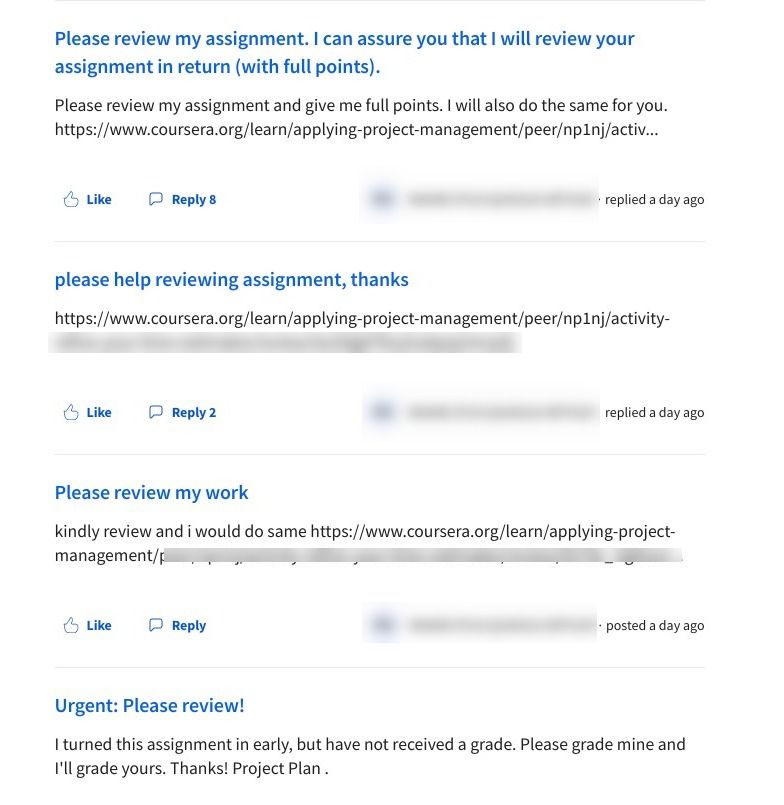

Massive online courses have not yet figured out how to implement feedback loops on the scale they are proposing. These things are very difficult to do at scale. In fact, in around two dozen online courses through a content provider, I have never seen one of these courses successfully pull off this kind of assessment. You'd think that maybe the discussion board features at these courses would be able to fill in the gap, on the theory that discussion boards get more useful as more people use them. But instead they look like this:

So the main thing that keeps online courses and certificates from eating traditional higher education's lunch right now is that the online providers simply haven't figured out assessment yet. Their assessment model, based on the ability of learners to complete their work in a "self paced" way --- which really translates into "with as little human interaction as possible" --- is fundamentally at odds with how humans learn. Traditional universities on the other hand have been doing this for centuries.

So as long as we keep doing this, traditional higher education is not in the kind of existential trouble some people say it's in.

...At least not yet.

However, as I put it in a conversation about this on LinkedIn, the first provider to successfully crack the code on authentic assessment at scale, wins. If Coursera dumps massive resources into a MOOC Manhattan Project, to build a system of assessment that engages thousands of learners at a time in feedback loop-oriented assessment, and it actually works when rolled out, higher education is not just in trouble --- it may be dead in the water. Given the financials we started this article with, and the partnerships with mega-companies like Google --- not to mention other partnerships involving traditional universities, as Udacity has with Georgia Tech --- this could happen sooner than we think.

Traditional higher education can't wait around for this to happen, or worse, continue to stand still or try to wind back the clock. Instead we must embrace the concept of feedback loops and learner-centered instruction at the human scale. This means, for example, taking seriously the concept of alternative grading approaches like specifications grading and ungrading. It means walking away from lecture as a primary means of instruction and instead embracing active learning. It means being mindful of class sizes. It means investing in faculty to give them the time, money, and energy to drive those feedback loops --- and changing the way we evaluate the performance of those faculty. It means, if you're a C-suite type, having serious conversations about, and making serious investments in, creating structures and cultures at the university that put all of the above at the center, as strategic priorities. Because they are.