Finding common ground with grading systems

This is a repost from Grading for Growth. I post there every other Monday (my colleague David Clark does the other Mondays) and usually repost here the next day. Check out the bottom of this post for some additional thoughts that didn't appear in the original!

As David and I write and engage with others about grading, there’s definitely a sense that the time is coming, and maybe is already here, for a wholesale change in how we grade in higher education. When David wrote last week about the profusion of alternative grading techniques that are out there, I think the sheer variety signifies a deep and widespread desire to make this change. People are realizing that reforming assessment and grading can have outsized results in improving higher education as a whole. It’s one of those places where 20% of the effort will produce 80% of the results.

But the variety can also be overwhelming. Instructors might say, I want to change my grading practice, but should I go with specifications grading? Standards-based grading? Ungrading? Contract grading? Most real-life approaches to alternative grading don’t fit neatly into any of those boxes, and often none of these general categories will be a perfect fit to your students in your classes. And how are we supposed to keep up with all these terms? Do you have to be an expert even to get started?

It seems smarter to focus on the overall ideas that unify these different approaches. So this week, rather than introduce another kind of grading practice, we’re going to pull back to a higher altitude and try to distill what all these ideas have in common and come up with a general framework for these practices. Not a “definition” of anything — there’s still too many idiosyncrasies and varied practices to hope for something that’s both precise and general — but instead a map, with room for interpretation, that stakes out some of the common ground that we seem to be walking together.

Common ground

Despite the differences in the ways that all these grading practices are worked out in real classrooms, what do they seem to have in common? Here’s what I see:

- Student work is evaluated against clearly defined and context-appropriate standards for what constitutes “acceptable work”. In other words, the systems are rooted in students knowing what acceptable work looks like, using standards that are professionally appropriate but scaled to the level of the student. Standards-based grading and specifications grading are obviously built on this principle (just look at the names). Ungrading advocates might disagree (see Alfie Kohn’s famous essay “The Trouble with Rubrics”). But even when ungrading, although you might not use a concrete rubric, you are still making decisions about whether student work is “good enough” or not. Presumably those decisions aren’t just made by “gut feel” (which is one way of saying “personal bias”) but through standards that you, as a content expert, believe are appropriate for determining quality. In other words, we’re all using standards. Ethics and common decency would say we should externalize those and be up-front with students about it, and so that’s part of the system.

- Student work, when evaluated, is given helpful, actionable feedback that the student can and should use to learn and improve their work. Feedback is the beating heart of all of these practices. Traditional grading looks at student work, assigns a number or a letter to it — and that’s all. It gives student work the silent treatment. In all these alternative practices, instead, the students’ work opens up a conversation and initiates a feedback loop.

- Student work doesn’t have to receive a mark, but if it does, the mark is a progress indicator and not an arbitrary number. The alternative practices we’ve mentioned here all share the realization that marks, if given, are just at-a-glance summaries of what the feedback says — nothing more. They are there primarily for convenience and for entry into a gradebook. In particular, these grading practices do not pretend that numbers assigned to student work (75%, 8/10, etc.) are numerical data. They are not. They are categorical data disguised in numerical form, like zip codes, and the statistical contortions used by traditional grading to convert those numbers into letter grades are fundamentally irrelevant and merely give the illusion of objectivity. (“Objectivity theater” is how it’s been described.) It would probably be better to dispense with marks altogether, as ungrading typically does, given their tendency to distract and demotivate students. But if we must put marks in a gradebook, they should be informative. They should be informative categorical data rather than fake numerical data.

- Students can revise, resubmit, or reattempt work without penalty, using the feedback they receive, until the standards are met or exceeded. All of these alternative frameworks are predicated on feedback loops. This seems to be their defining and essential ingredient. They don’t only have clear and appropriate standards and regular streams of feedback: They also allow students to combine their work, the standards, and the feedback and then try again. It’s in the trying again that grading turns into growth. And we don’t penalize this, because what kind of person penalizes growth?

Not a definition

There is a temptation at this point to look to the four observations I’ve just made and turn them into a definition of a general category of grading, with a special name, of which SBG, specifications grading, etc. are all instances. (David and I are mathematicians, after all — abstraction is what we do.) But I am going to resist that temptation, and I think you should too, for two reasons.

First, definitions are exclusionary by nature. When you define a thing, you draw a line between instances of that thing and non-instances of it, and the “canonical” instances tend to receive pride of place. This is OK in some situations (e.g. defining terms in mathematics so you can meaningfully prove theorems about them) but in other situations, especially education, it tends to be highly counterproductive because it locks people out unnecessarily. If you’re thinking of instituting a grading system that involves a lot of feedback and revision, but for whatever reason you still want to assign points to things, you shouldn’t feel left out of this conversation or pressured to do things a different way because a definition said so. If you’re an ungrader and feel that some of the observations above don’t quite fit what you’re trying to accomplish, you should still feel welcome at the table and able to have a real conversation about student success with someone who does specifications grading.

Second, definitions of educational ideas in my experience tend to derail people’s focus. I learned this when writing my flipped learning book. Flipped learning at the time needed an operational definition that made it possible for people to do research about it, and made it OK for instructors not to use video. So I came up with one; but a lot of faculty stopped asking good questions about flipped learning (What’s the best way to use class time if I’m not lecturing?) and instead focused on whether what they were doing was “real” flipped learning or not. So rather than give a definition of “Proficiency Grading” or “Awesome Grading” or whatever you might want to call it, let’s just not, for now, and focus instead on how best to do whatever it is we are describing here.

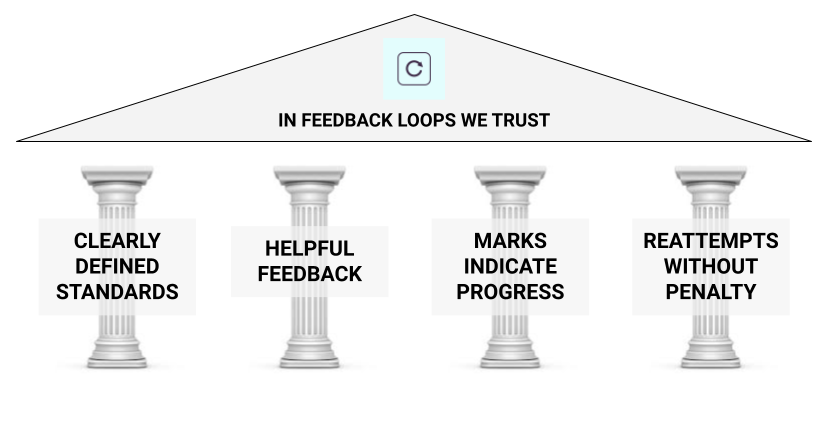

Four Pillars (beta version)

So we are setting up a big tent with a lot of room underneath for anybody who wants to think about the sort of grading approaches being described here. Stealing shamelessly from our friends in the IBL community, I’d like to close here by visualizing this “tent” as a building with four pillars.

(A graphic designer I am not.) As advertised, this is a beta version, not in any way guaranteed to be complete or even correct. In fact David has already informed me that I need to work on this some more. But that’s what the comment section is for, and anyway I think it’s more useful than a definition of a term.

In fact what I hope, is that in the near future, what we’re describing here won’t need a special term — it will just be “grading”, and grading using these practices will be so normative that it’s the departures from these practices that will need special terminology.

Some further thoughts:

- About that definition of flipped learning: It was important to have some operational definition of the idea at the time, and I think still is important now, because research was beginning to really ramp up on flipped learning but what people were actually studying was all over the map. In particular, there were emerging research definitions of flipped learning that insisted that students must watch video prior to group meetings, or else what's taking place isn't "really flipped". This was and still is misguided but that didn't stop the idea from taking hold, even in one of the most cited early research reviews on flipped learning at the time. I don't think we're to that same point with alternative grading practices – yet.

- As I noted in a footnote to the original article, in fact we have in places given this general concept a specific name: Mastery grading, or sometimes “mastery-based grading”. There are several issues with this term, none of which I am going to discuss here and now because every time it gets discussed it becomes politicized, which draws focus even further off the main point. Everybody wants to be the person who came up with "The Name" for this concept but we're thinking way too hard about The Name and not nearly hard enough about how to explain the underlying idea, implement it, and make it work with students. So focus on that instead.

- Regarding that last paragraph, credit where it's due: Sharona Krinksy, the main driver of the annual Grading Conference, is the one who’s said this the most about grading. I have said and still do say a very similar thing about flipped classrooms, that one day we'll just call it "the classroom". Again, maybe that day's arrived?

- There may be another level of common ground to explore here, and that's the path that these kinds of grading systems share with the natural, human way of learning anything, in or outside of school. I met my Fall 2021 classes for the first time yesterday and asked them two questions: (1) How they got to be good at the thing they are best at doing, and (2) what they were excited, curious, or nervous about in the class. For the first question, as always happens, students pointed out without any prompting on my part that we learn things through mindful practice, informed by failure and feedback. But then, every single student said they were both curious and nervous about the grading system. Maybe there's room for both, but the first point ought to be used to alleviate the nervousness in the second. We use a grading system like this because it's how you've learned your whole life. It's not "new", "unusual", etc. — it's as old as human learning itself. It's just not how we've played school up to this point.