Steps toward excellence: Structure and routines

This is part 5 in a series for educators who want to go from "perfectly adequate" online instruction to excellence, one step at a time, as we move from a forced migration to online teaching toward a more intentional approach in later semesters. Here's part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4.

A lot of what I've written in this series so far comes from what I've learned from the Quality Matters rubric for evaluating online higher education courses. The focus on learning objectives as the backbone of the course --- and then aligning activities, assessments, learning materials, and course tools with those objectives --- is straight out of the QM playbook.

But I'm not just copying what the QM rubric says. In my own teaching experience, both online and in-person, the best moments in my classes have come when the learning objectives are at their clearest and everything is aligned with them. Pedagogy is extremely important, but the results are constrained by our structures (or lack thereof), so that's why I've started with structural ideas in these initial steps toward (more) excellent online teaching.

Structure all the things

I'm going to deviate a little from the Quality Matters gospel and discuss a different aspect of structure. You might call the next step more infrastructure than structure:

Step 5: Structure the course into thematically-grouped modules, sequenced in a logical and cumulative order; and build a predictable course routine that is housed on a clear, accessible course calendar.

This sounds really boring, doesn't it? "Logical order"? "Predictable routines"? "Calendars", for goodness' sake? What is this --- an exploration of fascinating ideas, or a factory production schedule?

I get it; for us instructors, nothing says "intellectual buzzkill" like schedules, calendars, and routines. But remember we constantly have to view our courses from the learners' point of view --- not ours. From the learners' point of view, especially in these days where students are stretched perilously thin and are still trying to learn how to learn in an online setting, there is no fruitful exploration of fascinating ideas without scaffolding to help them explore. For this, learners need seemingly-pedestrian stuff like calendars and schedules, to feel safe enough to take the steps we want them to take.

What is a module?

This step of creating a logical and well-sequenced collection of course modules and creating course routines isn't explicitly in the QM standards. It's more from Dee Fink's workbook, "A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning", which has guided my own course-building for many years. In it, you'll find the germ of many of the concepts on the QM rubric including (and especially) the importance of clearly-stated learning objectives and alignment (Fink calls it "integration") of all other elements of the course with the objectives.

After going into considerable detail about learning objectives and alignment, Fink writes (p. 26):

After you have created the basic components of the course, identify ways of

organizing these activities into a powerful and coherent whole. This is done by creating a course structure, selecting or creating an instructional strategy, and then integrating the structure and strategy into an overall scheme of learning activities.

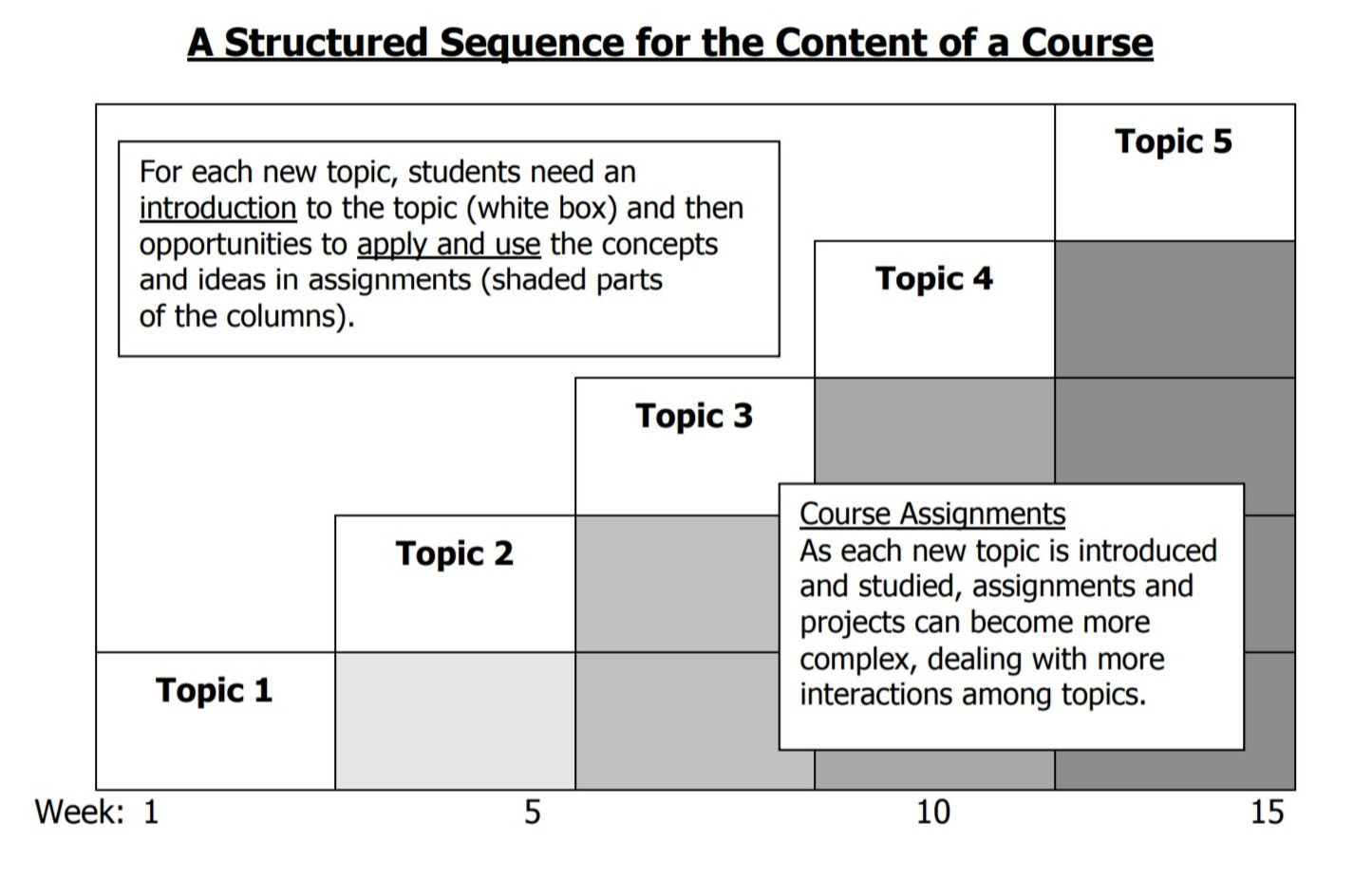

Creating a course structure simply means dividing the semester into 4 to 7 segments that focus on the key concepts, issues, or topics that constitute the major foci of the course. Then you arrange these concepts or topics into a logical sequence and decide how many weeks or class sessions to allocate to each one. One major value of doing this is seeing more readily how to create questions or assignments for students that gradually become more complex and more challenging.

Those "segments" are what we are calling "modules". The "4 to 7" number might be on the low side, depending on your course. I've found it helpful, if I'm teaching a 12- or 14-week course, to use between 10 and 12 modules, each corresponding to one week in the course. Each module should:

- Be thematically coherent. Each module should have an overarching question or idea that the module points toward, and all activities and assessments are oriented toward.

- Build upon each other. Fink makes the point that "as each new topic is introduced and studied, assignments and projects can become more complex, dealing with more interactions among topics".

- Have a similar set of learning activities and assessments. Students should be doing the same basic things in each module at roughly the same times (although the specifics may differ and the tasks may become more complex).

- Have clearly-defined start and end points that are consistent from module to module. This goes with the previous point, and goes a long way to building predictable routines.

Example from Precalculus

As an example, here's the module structure I used for a 12-week online "Functions and Models" (basically precalculus) course I taught last summer (direct link):

This was the first course I'd ever taught where I made the thematic grouping of modules explicit in the syllabus, and it was incredibly helpful for students and for me. At any point in a module, I could remind students why we were learning what we were learning --- for example we were learning logarithms because they are used to reverse exponential growth and decay.

Each module began on Monday morning at 12:01am and ended at 11:59pm the following Sunday. The learning activities were the same in every module:

- Monday and Tuesday: Students work through a Guided Practice exercise that involves reading, video, and a brief exercise to get to the main points of the reading and video; students also start working on a group problem that will be posted later in the week.

- Wednesday and Thursday: Students work in small groups on CampusWire on their group problem, which is to be posted by Wednesday 11:59pm. Thursday students engage in group discussion of those problems. Students also work during this time on weekly practice assignments (done using WeBWorK) assigned for the module.

- Friday: Wrap up all discussion of group problems and finish up WeBWorK assignments. There was also a Weekly Report due from each student involving reflection on their work from the module.

Saturdays and Sundays were always free. Students also worked on application problems that floated outside the module structure and had a flexible deadline structure.

This module structure wasn't perfect, and I ended up changing some things for the Fall 2019 version of the course which was offered in a hybrid format. For example, I changed the sequencing of activities so that if two sections of the text were covered in a single module, then students needed to complete all the activities for the first section before beginning the second.

But overall the module structure worked well, I think, because when we human beings are faced with a big job (like completing an online course) we tend to think of it as a task, when in fact it's a project that consists of possibly hundreds of tasks that have to be done one at a time. (Differentiating between tasks and projects is something I've brought up before in the context of getting grading done.) When a big job is broken up into component tasks, and we then focus on the next action rather than the entire job, only then does it become psychologically possible to complete the job. Having a modular structure to the course, and having sub-tasks within each module that always happen in a particular order, enables this for students.

Routines and calendars

Routines are a form of automation. I have a routine in which every morning right after I shower, I go get a glass of water and take my heart medications. I have a reminder set on my phone just in case, but because this is an ingrained routine I've built up over the course of a year, I rarely need to be reminded; it just sort of happens because I've programmed myself to do it, and I don't really think about it as such.

Students in online courses need routines, especially now as many students (and faculty) have been forcibly separated from all their routines. Routines not only lessen the crushing cognitive load that online students, especially those unused to learning online, experience; they also provide a handhold, a small but significant touchstone of familiarity that helps students feel at home, even if just a little bit. With a clear, dependable module structure, students can think less about what they are supposed to be doing and think more about actually doing it.

But those routines don't install themselves. To help students get into productive routines, anything with a date on it needs to go on a central class calendar. I use Google Calendar for my courses because it's free, ubiquitous, easy to use, and easy to share. In fact, here's the calendar from the Fall 2019 version of my Functions and Models course (page back to August 2019 to see stuff):

Using the same embed code I just use to put the calendar here in this post, I embedded the Google Calendar in a page on the course LMS; and students could add it to their own G Suite or just view it online. Changes or additions to the calendar update in real time anywhere it's embedded, so I don't have to pull down and re-post calendars if those changes need to be made.

I observed two rules about the calendar with my students. Rule #1 was anything with a date attached to it is on the calendar even if it appears elsewhere. Rule #2 was the calendar is always right, so if there was an apparent discrepancy in dates between two sources, the calendar was always declared the winner. This made the calendar the single source of truth about all things date-sensitive in the course, and therefore students never had to think about dates; they just went to the calendar. (The answer to all questions about when something was due was, That's on the calendar. Consequently I stopped getting emails about due dates about 2 weeks into the course because those emails weren't necessary.)

The common thread here is that routines and calendars reduce extraneous cognitive load on students, free their minds up to think about course concepts rather than procedures and due dates, and help them feel safer and more comfortable in the course.

In the next post, I'll mention some more about infrastructure, focusing on the course syllabus and the LMS.