Start the semester at Inbox Zero

The beginning of the semester is almost upon us, and you know what that means if you're a professor: Email, and lots of it. In the last 72 hours, I have gotten email from students about my courses; email from my department chair about our startup meeting; email from my faculty colleagues with questions about the startup meeting since I am now Assistant Chair and apparently I'm the person to ask; email from the Dean's Office; email from collaborators on research projects; plenty of spam email; and more. And this is just one of two email accounts I use, and the semester hasn't even started yet.

It is a real challenge to stay on top of all this email, and many faculty just give up. The number of emails in their inbox is a measure of the degree to which they've surrendered. I sometimes sneak a peek at the mail app icons of other faculty sitting next to me, and sometimes I reel back in disbelief: 100, 500, 1000, 2000, or even more emails sitting there in the inbox, like dinosaurs that wandered into the tar pits. I don't bring this up to shame people in this situation. But I do maintain that this isn't a healthy way to live, and in the spirit of starting fresh with a new semester, I offer a challenge to all who read this: Start the semester off at Inbox Zero.

What is Inbox Zero and why would I want it?

Inbox Zero is the state of having your email inbox empty, or nearly empty, at all times. It also refers to the mindset of approaching email with rigorous, disciplined management rather than just letting stuff accumulate.

Sounds like work, you might say. Why bother, and what's wrong with a big inbox? As productivity master Merlin Mann put it, the "zero" in "Inbox Zero" doesn't necessarily refer to the number of emails in the inbox but rather the amount of time your brain is in your inbox. When your email inbox has unresolved items in it, part of your brain is there --- in your inbox and not focused on more important things like teaching, service, or research. Conversely, when your inbox is empty or nearly empty, and you have built a habit of disciplined management regarding your email, your attention is no longer stuck on your email, and you're much freer to use your brain to focus on the things for which your brain was actually designed.

But I don't really think about my email that much, you might say. But what psychologists have learned is that these unresolved emails produce a drag effect on our memory and attention, even when we aren't thinking about them. The psychological phenomenon known as the Zeigarnik effect, which has been studied by psychologists since the 1920's, states that uncompleted or interrupted tasks are more easily remembered than completed tasks. Another way to put this is that unresolved tasks continue to draw attention and take up memory even when we are not consciously aware of them.

Applied to email, this means that when you get an email message and fail to "resolve" it --- for example, you don't open it; or you open and skim it but don't decide on what to do about it --- that message, even when you've moved on to working on something else, continues to draw from your limited stores of memory and attention, like a computer program that continues to run in the background and eat up CPU cycles. The cumulative impact of the Zeigarnik effect can be devastating: One unresolved email may not affect you noticeably, but multiplied over dozens of emails per day times 5-7 days a week, and the dispersion of attention can grind you to a halt.

I've felt that cumulative impact myself. Before I started getting serious about managing my email, the messages would pile up and it was almost like having a cognitive disorder: I'd forget events and meetings; I'd find myself unable to respond to student emails in a timely way; I'd find it hard to concentrate on research or teaching because I was constantly wondering about the unknown unknowns that might still be lurking like a time bomb in my inbox.

Far from being some sort of humorous aspect of academic life, having an inbox that is significantly far away from zero is harmful to almost every aspect of being an academic. It lessens the effectiveness of our thinking, stresses us out, creates pointless work for ourselves, and has a negative impact on students, colleagues, friends and family. But there's good news: Far from being an inevitable burden, attaining Inbox Zero is within the grasp of each person reading this --- even before the first day of classes. And it's not really even that hard.

Getting set up for Inbox Zero

If you're willing to try getting to Inbox Zero, the first thing to grasp is the game plan: The overall workflow behind managing stuff coming into your inbox.

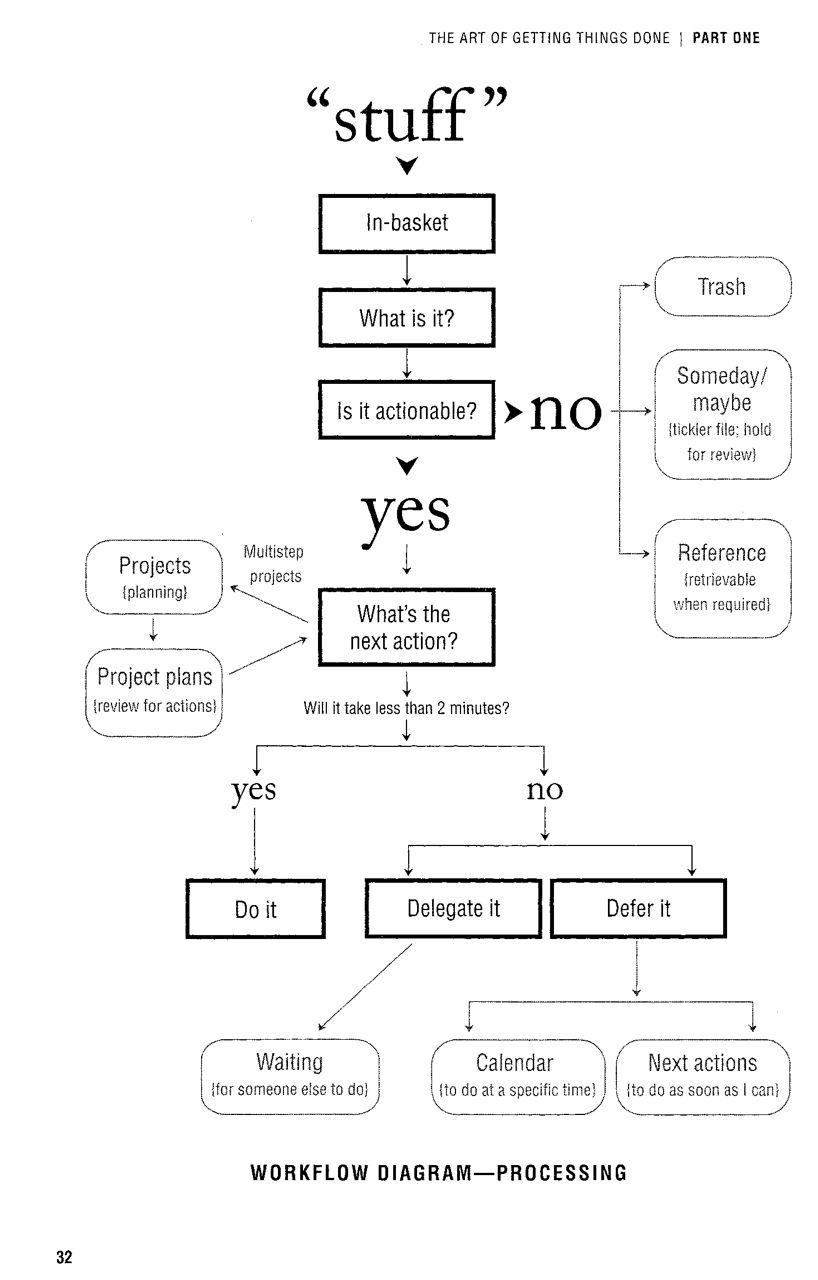

The following flowchart is a picture of how effective email management works, It's taken from David Allen's book Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity:

Look at your inbox and then look at any single email in it. That email either actionable --- meaning that the email contains something that needs to be done by me --- or it isn't. If the email is not actionable, there are three ways to categorize it:

- It's trash. This refers to emails that have no real pertinence to me now or probably ever, like spam, or announcements for events I'm not going to attend, and so on. Once you determine an email is trash, delete it.

- It's a Someday/Maybe item. Some emails suggest something to do, but it's not pertinent now but rather something to think about later. Examples include suggestions of books to read that you don't intend on reading soon, but might someday; or research questions you might one day try to investigate. For these emails, put the gist of the email into a list called the Someday/Maybe list and then delete it.

- It's reference material for something pertinent now. These emails don't contain any actionable information in them, but are needed as reference to something current. For example, I'm attending a conference this week and I got an email yesterday from the organizers with my registration code. I need to keep that handy, obviously; but it's not "something to do". In these cases, file the email away in a trusted reference system so it can be retrieved when needed.

With email, there are several easy ways to implement reference systems for messages that fall into this latter category. If you are using Outlook, you can set up folders for your reference material, organized in whatever way makes sense for you (e.g. one folder for student emails, one for research materials, etc.) and then just drag and drop the email into the folder once you've identified it as reference material. You can also use folders in GMail. My preferred system is Evernote. Evernote is organized by "notebooks" (like Outlook folders) as well as tags, and it has an incredible search capability. You can forward emails to a special address that will send them to Evernote and specify the notebook and tags by editing the subject line of the email. So when I find I have an email that's not actionable but is needed for later reference, I just forward it into Evernote with the notebook and tags set, and then delete the email from my inbox. If/when I need it later, I can just search it up in Evernote.

I find that the majority of email that comes into my inbox is non-actionable. This means that most of the email I get is going to be deleted after reading, or sent off to Evernote (and then the original email is deleted). Neither of those tasks (deleting or moving into reference) takes longer than 60 seconds most of the time. If you're wondering how much work it's going to be to zero out your inbox, this should give you some hope.

So what happens if the email is actionable? For this, we need to review parts of the Getting Things Done (GTD) philosophy which I have written about before at length. Briefly, when you detect an actionable item in an email, ask yourself whether the item is a single task, or something that has multiple tasks involved. The latter is what we call a project. If the email is calling for a project and not a task, then break the project down into component tasks; then find the one task in that list that is the next physical action that you can perform that moves the project to completion; this task is called the Next Action for that project.

Each project should have a list, on paper or on the computer, that has all of its actions contained in it and the Next Action highlighted somehow. You should also make a list of all tasks that are either Next Actions for your projects, or stand-alone actions that are single tasks. It's this "master list" of next actions that we focus on when we are working.

So now, the email has been converted into either a single task, or a project with one designated task to do next. Look at that task:

- If the task can be completed in two minutes or less, go ahead and do it right then. (This is known as the Two Minute Rule.)

- If the task can't be done in two minutes or less, then either delegate it to someone else, put it on a calendar to be done later, or put it into the master list of Next Actions to be done as soon as you have the time.

The full details of working with the next actions list is the subject of my entire GTD for Academics series. Summarizing like this hides some of the nuance, so I invite you to read the whole series for a full look at how this works.

Zeroing out your inbox

Once you understand the basic process of categorizing and processing emails and have set up a reference system and next actions lists to hold your emails and the information contained in them, it's time to do the deed and get the inbox down to zero.

Clear off an entire day this week or weekend to set aside for the initial blitz of clearing out your inbox and getting everything in its place. Then go through this process:

- Start at the top of your inbox (i.e. the most recent entry). Don't cheat and skip the emails that look hard to deal with.

- Determine whether that email is actionable or not.

- If not actionable, decide whether it's trash, something for later, or something you need for reference. If it's trash, delete it. If it's for later, put it on the Someday/Maybe list and then delete it. If it's reference, move it from your inbox to the appropriate place in your reference system. In all three cases, the email is out of your inbox.

- If actionable, then extract all tasks from the email, either as standalone tasks or as actions in a project and process each task (standalone or Next Action) according to the steps above. Then delete the email (or send it to reference).

- You are now done with that email, and it's out of your inbox. Repeat with the next one.

- Continue until you have no more emails in your inbox.

This is obviously not as simple as it looks, and it takes some mistakes and getting used to. When I first started practicing this process several years ago, I stumbled over the steps and was confused fairly often about how to proceed. It would take me a few minutes to process each email; and the initial zeroing-out blitz I mentioned above took up an entire Saturday. But, I ended that Saturday with a completely clear inbox for the first time ever, and it felt like I had climbed Mount Everest. I practiced this process more and got the hang of it, it became a lot easier, and now it's second nature. As I've found since then, maintaining a zero inbox is a whole lot easier than getting it there in the first place. My inbox now rarely has more than 20 emails in it at a time, and I zero it out at the end of every working day, which takes me about 15 minutes.

If you want to see how all this works, check out this video I made for an earlier GTD post, which shows me actually zeroing out my inbox in real life, while I talk through the process and my decision making steps:

A way of life

Inbox Zero is sort of a way of life that is based on, and leads to, a state of relaxed focus in which your mind is free to focus on the important things, free from the nagging pull on attention and memory that email exerts on us, whether we are consciously aware of it or not. Academic work is hard enough as it is. There's no point in making it that much harder by placing unnecessary burdens on our minds.

I hope you give Inbox Zero a shot, and if you do, I'd love to hear your stories about how it went and what it's like. Send those to me (and fill up my inbox!) at robert.talbert@gmail.com.