Working mindfully with projects

So far in the Summer Challenge, we've reviewed two habits about work:

- Capturing: Whenever something gets our attention, we don't leave it in our brains but capture it into an external holding place.

- Clarifying: We loop through each item in each inbox and clarify it. What is this? What does it mean to me?

Practicing these two disciplines on a daily basis is critical for building the habits that will make the next academic year a better experience for many of us. I hope you've been successful in this; or at least you are trying to be.

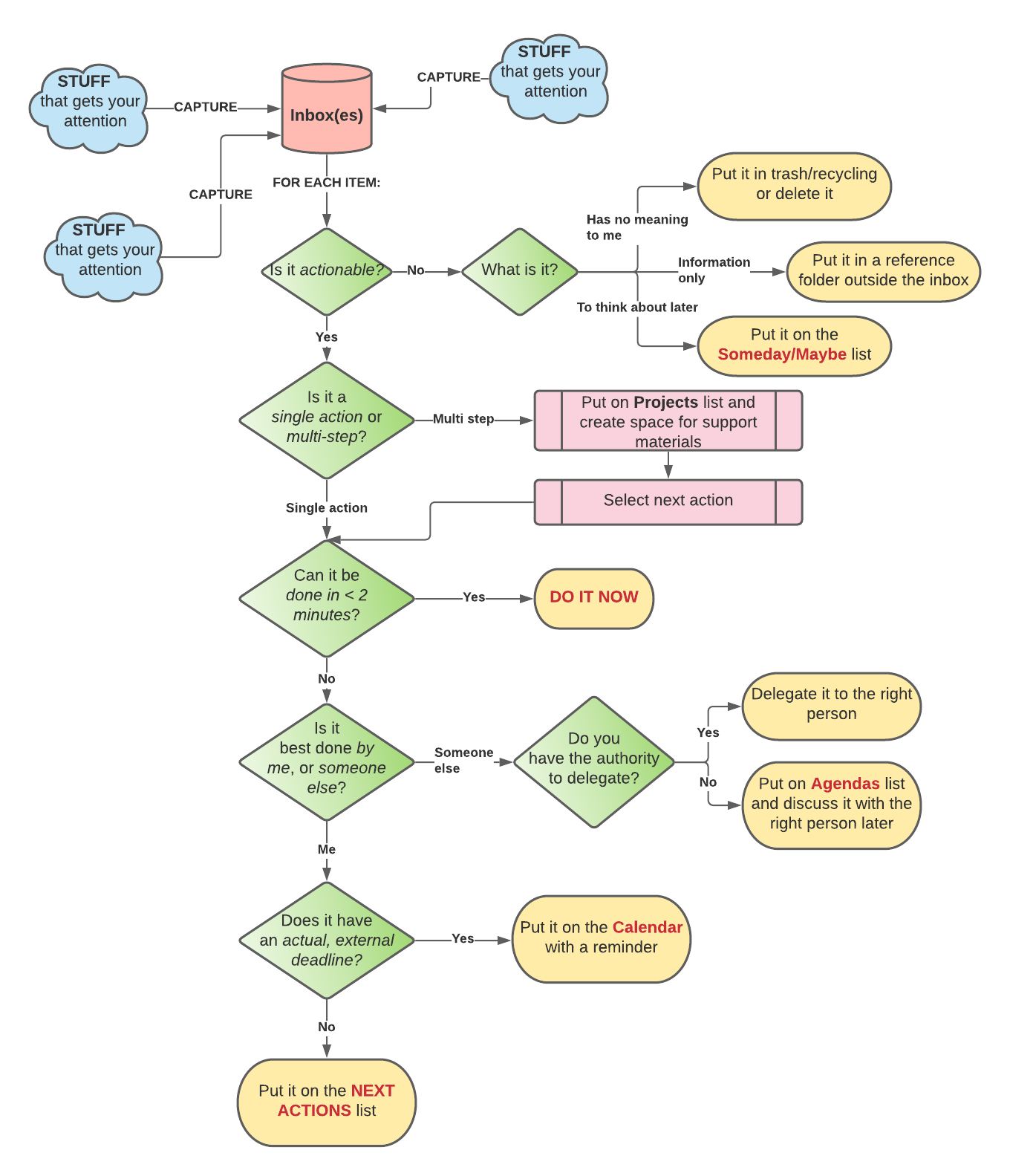

This week we need to return to a step in the clarifying process that we didn't fully flesh out last time. It happens when you realize that a thing you've captured is actionable, but it's a multi-step process rather than a single action. We refer to such things — stuff to do that we want to get done within a year's time (i.e. not something that's better suited for the Someday/Maybe list), and which takes more than one step to complete — as projects.

Everyone has projects; academic folks have lots of projects. Writing research articles, grading tests, preparing lessons, specific assignments on committees, and learning new subjects are all examples of projects. So are personal items like planning vacations, making major purchases, and doing significant things with family and friends. Both personal and professional projects are equally significant for our overall health. We forget this many times, and failing to handle projects mindfully wherever they show up usually causes us to focus entirely on work, and forget about everything else. That doesn't end well, as a lot of us discovered last academic year. So it's important to be in control of these projects, or they will control us instead.

Project handling

If you identify an item as a project and not just a task as you go through the clarifying loop, there's a pretty simple basic strategy for handling it:

- Put it on the Projects list (which you've already done) and create space for support materials if needed. Sometimes projects are small enough that you may not end up with documents or emails that pertain to it. But most complex projects have documentation and messages that may need to be accessed for reference. If the project is like that, then make a space where those materials will live — a folder (physical or electronic) for files and an Outlook folder or GMail label for messages is often enough.

- Make a list of all the actions needed to complete the project. Since it's a project, there is more than one action. Maybe there are only two; but make a list of all the ones you can think of. Try to capture as many tasks for the projects as you can, but don't worry about whether you've left any out. It's likely that you'll modify this list later; we'll discuss that when we talk about reviews.

- Of those actions, determine the next, physical action that can be done to move the project closer to completion. This action is called the next action of the project. Note that a project's next action is not necessarily the most important, time-consuming, or urgent action that can be taken — it's just the one that can be done next. In fact I've found that many times the next action on a project looks pretty insignificant.

- Pop off the next action and continue the clarifying loop with it. The next action is a single action by definition, so continue interrogating it with our battery of questions discussed last time, just as if it were a stand-alone action not connected with a project: Can it be done in two minutes or less? Is this for me, or someone else? Does it have a deadline? If it makes it through the filters of clarification, it will end up on the Next Actions list that you created last time. That list now will consist of next actions that are not project-related, along with those that are.

As the philosophy of Getting Things Done teaches, the most important thing you can do with a project, no matter how simple or complex it is, is to ask: What is the next action? When confronted with a large project (or a small one), this question cuts through the fight-or-flight response we experience and orients us toward doing something that will move the project forward.

Adding this project-handling step into the clarification loop modifies our flowchart as shown below. The new items on the chart are in pink.

Example: Screencasting

Here's an example of how this worked out for me last week. I was thinking about a workshop I'm doing in August whose materials are due to the host by July 15, and I realized that I needed to make a new video for the workshop to go along with the ones I'd already made. This thought had my attention, so I captured it in my notebook: Make new screencast about learning objectives. Later on, I was processing my inboxes (which includes my notebook) and needed to clarify what to do with this.

Is it actionable? Definitely — in fact I need to get working on this, because July 15 will be here soon.

Is it a single action or multi-step? Here's where the new parts of the process come into play. Some screencasts — the quick-and-dirty ones where I just hit "Record" and talk while writing on a digital whiteboard — might be single actions, but not this one. This video needs to be carefully made for the audience I'm prepping it for. It needs to be done soon, and definitely takes more than one step — so it's a project, not a task.

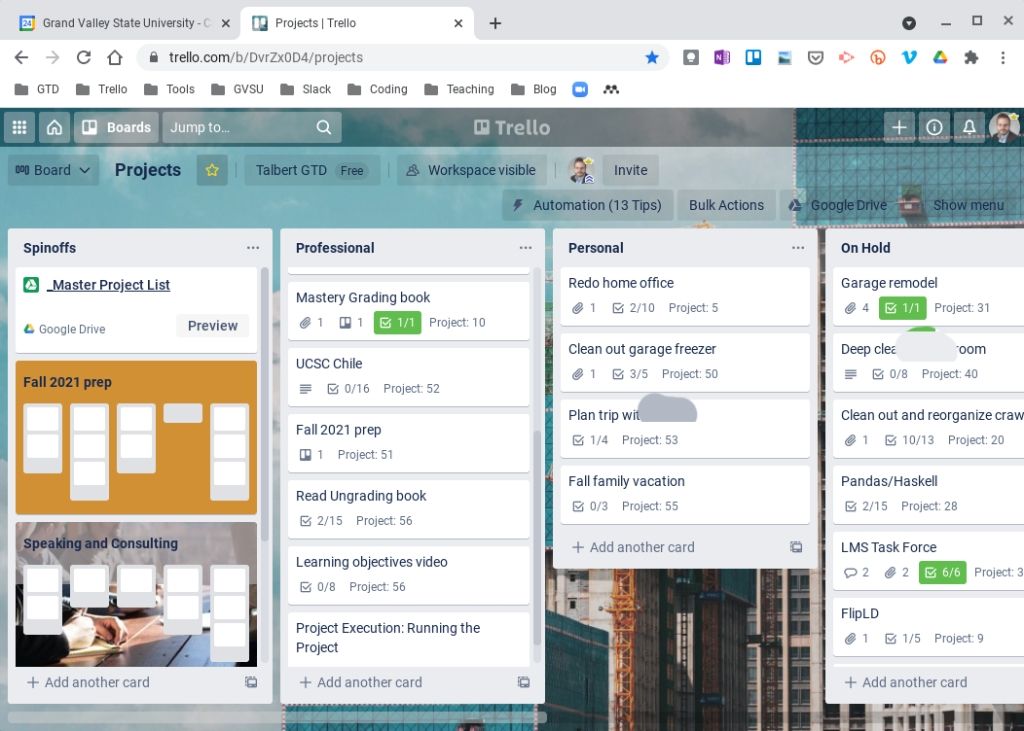

The first thing is to give the project its own space by adding it to my Projects list, which I keep in Trello. It's the second from the bottom in the "Professional" list:

This is actually a board in Trello, with separate lists for Professional and Personal projects along with a list where I park projects that aren't active, and a few other lists. Each project is a card on one of these lists, and I can attach things like files, notes, and checklists to the project's card. But something simpler would be fine too.

I also created a folder for this project to contain all the audio, video, and text files I'll use in the creation of the screencast. I would normally also create a Gmail label for this, like I do for most projects, but I don't plan on emailing anybody about this, so I skipped that step this time.

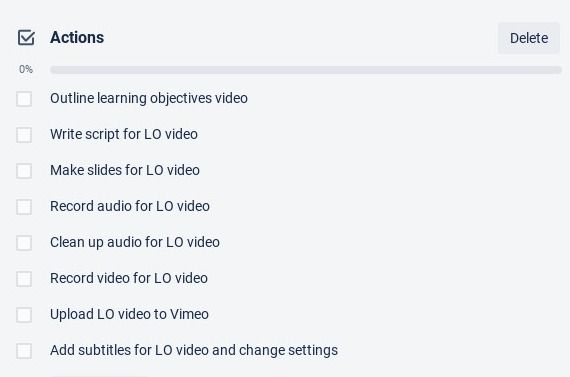

Speaking of checklists, the next thing was to brainstorm all the actions needed to complete the project. Making screencasts for me tends to involve the same steps each time, so I have this actions list stored as a template that I can just copy and re-use:

Now the important question: What's the next action? What is the next, physical action I could take that would move this project forward? In my estimation it's the first thing on the list: Outline learning objectives video. It's not always that easy; sometimes the actions list I brainstorm doesn't occur in any kind of order.

Finally, I take this next action from this list and continue on with the clarifying process. Can it be done in less than 2 minutes? Probably not. Is it for me to do, or someone else? That would be "me".

Does it have an actual, external deadline? Well... yes, but actually no. The entire project has a deadline (July 15) but this single next action does not. Obviously this part needs to be done by July 15, but if I wait until then to do just the outline, I'm screwed. So the single action of write the outline is something that needs to be done as soon as possible, when I have the time, space, tools, and energy level for it (foreshadowing the idea of contexts, which we'll discuss in a later post) and definitely well in advance of July 15 — but there's no actual deadline there.

As I do daily and weekly reviews (to be discussed soon) I'll monitor whether this item can continue to sit on the back burner or whether it needs to be elevated in priority. In fact I can already tell this will be a priority item for next week (June 28-July 2) if I don't get it done this week (which I probably won't at this point). But I won't stick a deadline on this, because there isn't one, and there's nothing to be gained by creating a fake sense of urgency by pretending it did.

So this next action ends up, appropriately, on the Next Actions list. I keep my Next Actions in Trello as well, as a board with multiple lists kind of like my Projects board, but I'll save that discussion for later.

Why put this much energy into managing projects like this? I can think of at least two very good reasons.

- This process allows you to use small pockets of time effectively. While I don't think it's healthy to utilize every moment of time for finishing tasks and projects, it's also definitely the case that we spend a lot of small pockets of time — 10 minutes here, 20 minutes there — on things that add no value to our lives, for example mindless web surfing or Twitter doomscrolling. Breaking a project into component tasks and isolating the next action, and then doing just the next action, is a way to redeem those lost pockets. I may not have the 4-5 hours it will take to complete that screencasting project in a single, uninterrupted block, even in the summer. But I am confident that, even maybe this afternoon, I will be able to set side 15-30 minutes to write the outline and then save the rest for later.

- This process makes completing projects more psychologically possible. Even if I did have a 4-5 hour block of uninterrupted time to do this screencast, it's such a big undertaking that, despite how many times I've done it before, my instinct is to put it off. Instead, by decomposing the project and isolating the next action, and then only focusing on that next action, I'm just doing one simple thing at a time. We don't "do" projects — we do actions.

A third reason for doing this is simply that it keeps you appropriately engaged with the project itself. It's quite easy to capture an idea, but then it can get lost or forgotten because we leave it in our email inbox, or on a list without ever coming to terms with what we are supposed to do, and especially what to do next. If something is important enough to capture, then it deserves regular, sustained attention and this process provides that.

Another example of this process in action in a familiar setting is grading. I wrote this article a while back about treating grading as a project, and if you want to know more, check it out.